In Taijiquan (太極拳) the concept of harmonizing yin (阴) and yang (阳) is commonly given in dualistic statements like having neither excess nor deficiency. But avoiding excess (yang) and deficiency (yin) means that one needs to be where yin and yang meet/unite. When the energies are united, then hard (yang) and soft (yin) mutually help each other (刚柔相济 gang rou xiang ji).

Practitioners often view yin and yang in a dualistic manner concerning oneself and one’s opponent. Phrases like “use soft to overcome [or control] hard” (以柔克刚 yi rou ke [or 制 zhi] gang) further this perception by reinforcing the view that “internal” styles like Taijiquan should be soft relative to “external” style opponents who are hard. But there should also be a unification of yin and yang (e.g. soft and hard; passive and aggressive; receiving and issuing; retreating and advancing; etc.) within oneself.

Uniting yin and yang results in non-duality, and is sometimes called the “middle way” or being neutral. On a large scale this concept can be illustrated by one side of the body receiving/neutralizing an opponent’s force and using this to turn one’s body such that the other side of the body simultaneously attacks that opponent (making the defense and attack one action). However, uniting yin and yang within oneself has many degrees which can vary from large and obvious to being so small that it is unnoticeable to an outside observer.

I will begin with swordsmanship to better illustrate the concept of uniting yin and yang because, when using a single weapon, the complexity of interactions is much more limited, and therefore clearer to see, than weaponless combat where many simultaneous interactions, through multiple points of contact, often occur. Since Taiji saber/dao (刀, refers to the single edged sword and is sometimes called a “broadsword”) often spars with limited blade contact, it can provide a clear example for using the middle way in one’s spacing/distancing with an opponent.

In western fencing matches, observers often see the competitors lunging forward to attack when they think that they may have an opening, but then jumping back to try and get beyond the range of their opponent’s attacks or counterattacks. This is using primarily yin or yang; a separation of these qualities.

For Taiji saber/dao we may instead try to unite yin with yang by maintaining a closer distance that allows a practitioner to evade (or deflect) the opponent’s attack while remaining within counterattacking range. We do not want to disengage (jump out of range) because that would represent just yin. Likewise we cannot get too close (too yang) since the opponent’s edged weapon can easily cut us if it makes contact. Our retreat (yin) should contain the potential to counterattack (yang); our attack (yang) should not be over-committed and should contain the potential for changing to defense (yin) without getting too close to the opponent.

We seek to maintain a range that allows us to evade the opponent’s powerful saber/dao attacks while retaining the ability to counterattack. We hope their attacks leave them vulnerable to counterattacks, rather than us moving away merely to get out of range. We want our defense to set up our offense. In practice, some counterattacks are nearly simultaneous with the defensive movement because, as soon as the opponent can reach us with their weapon, we also are within range to reach them. Often this translates into intercepting their wrist (截腕 jie wan) since it is the closest body part to us.

This principle of maintaining the range rather than retreating outside of attacking range, is sometimes expressed by dodging with one’s body while attacking with the saber/dao, often using a back weighted posture when attacking. This can also be expressed by leaning the body backwards to avoid the opponent’s attack and returning to upright in order to be within range when counterattacking; or by lifting a leg to avoid a cut and stepping back down when counterattacking. Depending on one’s forms and training drills, many other techniques illustrating this principle may be practiced.

This principle of maintaining the range rather than retreating outside of attacking range, is sometimes expressed by dodging with one’s body while attacking with the saber/dao, often using a back weighted posture when attacking. This can also be expressed by leaning the body backwards to avoid the opponent’s attack and returning to upright in order to be within range when counterattacking; or by lifting a leg to avoid a cut and stepping back down when counterattacking. Depending on one’s forms and training drills, many other techniques illustrating this principle may be practiced.

Because of its emphasis on positioning and timing, saber/dao training can be viewed as being the foundation for all short weapons. Sword/jian (劍 double-edged straight sword) can be somewhat more complex since the weapon is not swung as powerfully or with as much momentum as the saber/dao, and is therefore better suited for techniques that attempt to control the opponent’s weapon through deflections and control through contact. Despite their differences, sword/jian employs skills acquired from learning saber/dao.

Single sword/jian sparring can be used to illustrate uniting yin and yang in a more complex situation, that of interacting with a single point of contact with the weapon of the opponent. In addition to saber/dao distance and timing skills, now the two participants should add the skill of uniting yin and yang at the point of contact between their swords. Practitioners should have yin and yang harmonized around the contact point of their own sword/jian, as well as harmonizing with the energy of the opponent’s sword/jian.

Harmonizing yin and yang at the contact point is often achieved by pivoting. If the root third of the sword/jian (the proximal, or third of the blade that is closer to the handle) is deflecting the opponent’s blade towards one’s side, then the tip third (distal, or third closest to the tip) is often pivoted to remain pointed towards the opponent. Likewise, if the tip is moving sideways, then the handle of the sword/jian often pivots towards the opponent.

Pivoting the sword/jian around the point of contact with an opponent’s blade means that there is yin on one side of the contact point, and yang on the other. One portion of the sword/jian is moving in one direction while the other side is moving the other direction. As long as there is a pivot at the point of contact, the sword/jian will have yin on one side and yang on the other, i.e. the pivot at the point of contact with the opponent’s blade will be the dividing line between yin and yang, and this is represented by the “s-curve” line dividing the two halves of the standard taiji diagram (taijitu 太極圖).

When defending while pivoting at the point of contact with the opponent’s weapon, one is more yin and would be on the s-curve in the bottom half of the accompanying illustration. When attacking while pivoting at the point of contact with the opponent’s weapon, one would be more yang and would be on the s-curve in the upper half of the diagram. By pivoting at the point of contact with the opponent’s blade, one can maintain the potential for both defense and attack simultaneously, even though either energy may dominate any particular interaction.

When defending while pivoting at the point of contact with the opponent’s weapon, one is more yin and would be on the s-curve in the bottom half of the accompanying illustration. When attacking while pivoting at the point of contact with the opponent’s weapon, one would be more yang and would be on the s-curve in the upper half of the diagram. By pivoting at the point of contact with the opponent’s blade, one can maintain the potential for both defense and attack simultaneously, even though either energy may dominate any particular interaction.

This pivoting can be practiced during “sticky” sword/jian free play, a type of practice that is fairly common in Taiji jian classes that use interactive drills and free play. Pivoting can be employed even when practice involves breaking contact with the opponent, such as when maneuvering while keeping the tip of one’s sword/jian aiming at the opponent.

If, instead of pivoting, a practitioner tries to block an opponent’s blade to the side by moving the entire sword/jian towards the side, then only one energy is being expressed and one becomes susceptible to changes that the opponent may make (like pivoting around the block in order to attack). Likewise, if one over commits to an attack without consideration of continuing into defense then, if the attack fails, they will be susceptible to the opponent’s counterattack. These vulnerabilities are due to separating yin from yang, doing one or the other rather than harmonizing both together.

Of course, practitioners should also harmonize with their opponent. When opponents emphasize attacking, practitioners should balance it with yielding and neutralization. When they retreat or leave gaps, practitioners should advance and flow into the spaces that the opponent collapses away from.

When we engage in weaponless interactions, all of the preceding qualities should be maintained in order to harmonize yin with yang. It is the spacing and timing, and interaction at the point(s) of contact, that allow us to use sticking and adhering, connecting and following (粘黏連隨 zhan nian lian sui), which are principle characteristics of Taijiquan interactions with opponents.

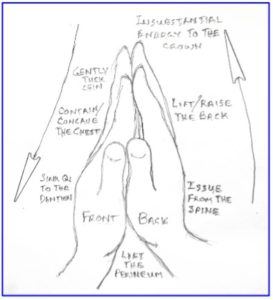

Maintaining harmony between yin and yang allows practitioners to maintain their six directions, i.e. balancing up and down, left and right, and forward and backward. A properly inflated ball, due to its inflated spherical structure, maintains harmony in all directions, but it is much more difficult for humans to do so. We want to harmonize the opposites so that we do not over commit to one or the other. We want to maintain yin plus yang rather than separating into yin or yang.

The harmony between yin and yang also allows us to avoid butting against (resisting, being excessive, having too much) and losing connection (running away or separating, being deficient, having too little). This is reflected in sayings like don’t separate or resist (不丢顶 bu diu ding) and don’t butt against or collapse, neither losing nor resisting (顶匾丢抗 ding bian diu kang).

The uniting of yin and yang is also reflected in the saying “stillness in motion, motion in stillness” (靜中有動 動中有靜 jing zhong you dong, dong zhong you jing). Yin is associated with stillness while yang is associated with movement, but neither is completely separated from the other. We want to use stillness when movement is not needed and the appropriate amount of movement when warranted. We want to maintain a calm (yin) mind even while moving (yang) quickly and with agility.

The relationship between stillness and motion can be illustrated with the ancient taiji diagram (below left) where the yin and yang energies cycle around a clear center. The “central equilibrium” (中定 zhong ding) of one’s body is analogous to the clear center and remains still when the yin and yang move around it. This unites yin with yang. It can also be likened to the functioning of a wheel, like the antique Chinese wheel pictured (below right). The wheel’s center, which attaches to the axel, stays relatively still while there is large movement at the rim of the wheel where it contacts the ground while turning forward or backward.

When referring to the practitioner, this relationship is illustrated by this center of one’s body and the periphery. It is also used in relation to an opponent. The Taijiquan practitioner can remain relatively stationary while the opponent is controlled in a manner that moves them around the periphery (like the periphery of a ball moves things around its center). Small movements can effect large changes.

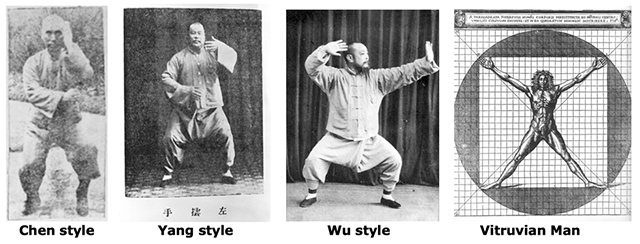

It should be obvious from the diversity of the information presented above, that uniting yin and yang in Taiji is a broad philosophical concept that defines most of what we do in our art. A variety of practices (like weapons work) can aid in the understanding of these concepts. Different Taijiquan styles, as well as different schools, have varying emphases and interpretations of the basic rules of practice. Therefore it can be beneficial for students to be exposed to numerous viewpoints and concepts, in order to more fully incorporate the harmonization of yin and yang into their personal practice.

Check out our other training articles!