Slanted FlyingJournal of Tai Chi Chuan

Training

Taiji Saber (刀 Dao)

One quality associated with internal martial arts is amplifying physical actions while reducing effort. This can still be done with the heavy saber, and the arm should be controlling or guiding the saber by letting the momentum of the movements power the blade rather than powering the blade primarily with the arm. Rather than stopping the momentum of the saber, spinning one’s body around and/or swinging the saber around the body lets the momentum continue without relying on arm strength. Springing or leveraging the saber off of the body adds power without much extra effort needed.

The body should retain its elasticity and the mobility of the joints even when producing powerful chops and slashes. The alignment and support of one’s skeletal structure should be maintained in order to produce unified movements. However, because of the weight of the saber and because it is used in such a powerful way, the saber should develop one’s spine and upper arms. The spine becomes the axis for movements and gravity and momentum causes the saber to move; the movement of the saber then leads your body’s turning. Sometimes the saber leads the body and other times the body leads the saber.

Other “internal” qualities that can be utilized when using a saber include rooting or grounding and centering, whole body three dimensional actions, and even calm relaxing even when exhibiting fierce determination. The fierceness of the saber, combined with the emphasis on agile stepping, reflect the enraged tiger charging down a mountain quality associated with this weapon. Practitioners should have brave determination rather than rage, and one should be vigorous and agile (like a tiger) with changeable power rather than being unyielding and direct.

When using a single saber in one hand, the free hand needs to follow the movements by having assisting or counterbalancing movements. Sometimes the free hand needs to grab the opponent or their weapon, and sometimes this hand assists the weapon wielding one by joining the hand, pommel, wrist, or the dull edge of the blade. The hands and eyes should combine in harmony with the form and footwork.

Strategically the saber typically uses evasion rather than deflection when facing another saber. But against long weapons like the spear, the saber is a short weapon that is used like a long weapon. The saber deflects an opponent’s spear while the saber wielder moves closer, and within the spear point, and then counterattacks when within range by using many of the wrapping, coiling, spinning, or sliding techniques to change from defense to offense.

Because the saber is commonly used against a spear, having extension in one’s body and through the saber is important. Still, practitioners should be able to control the point of emphasis along the saber so that the tip (e.g., for thrusts), the distal edge (e.g., for chops), the proximal portion of the blade (e.g., for blocks or pivots), and even the guard (e.g., for blocks) and hand (e.g., for defensive evasions) can be differentiated from each other.

The powerful chopping and hacking techniques of the saber are best used against unarmored opponents, although some ability to thrust is still retained. Thrusting is better against armor than is cutting or slashing and is better with sabers that do not have much curvature of the blade.

Many saber forms emphasize intercepting or chopping an opponent’s wrist initially since this is typically the closest body part of a weapon wielding opponent. The opponent’s defensive movement used to avoid the cut to the wrist often creates an opening that can be used in a follow-up attack to strike their body. The attack to the wrist is sometimes considered the yin (阴) attack whereas the follow-up attack to the body is considered the yang (阳) attack.

Attacks that utilize a blade orientation that corresponds to the palm in or up, like when one’s hand/arm is embracing something or pulling it in, typically are less powerful and can be considered as yin techniques. Conversely, blade orientations with the palm down or out, like when pushing something away, are typically more powerful and can be considered as yang techniques. Other yin and yang considerations are combining soft and hard in harmony and combining slow and quick movements while using relaxation for agility even when using powerful and relatively inflexible saber techniques.

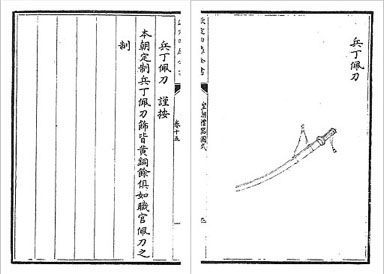

Finally, sabers used by the military typically had a wrist cord/lanyard (系子 xizi) rather than a saber cloth/colors (刀彩 daocai), as the following page in the Qing official regulations illustrates. Most late Qing and Republic period sources that show sabers (photos, film, drawings) do not include cloths attached to the saber, and some that do show cloths are too short to be used for anything other than decoration. Saber cloths apparently did not come into prominence until more recent times with performance oriented displays of martial arts.

However, some early sources do show longer cloths that could possibly be used for combat related functions like pulling on it with the free hand to change the leverage for controlling the saber, similar to touching or grabbing the pommel for certain techniques. Longer cloths could also be used to wipe off blood, could possibly distract the opponent by having a colorful, fluttering item to catch their eyes and attention, or could be tied around the wrist and function similarly to the military wrist cord/lanyard.

Practitioners should consider the inherent characteristics of the weapon being used as well as conforming to Taijiquan principles.

Don’t forget to check out our great training articles!