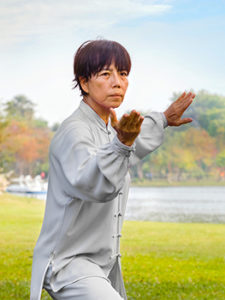

The ancient martial art Tai Chi, long a means of gentle, meditative exercise, is riding a recent wave of popularity by physical therapists and other individuals interested in using it to rehabilitate injuries and promote health. Tai Chi, which has roots dating back to 13th century China, has been the most popular health regimen to keep an aging population healthy in China, as it requires no special equipment and can be done almost anywhere. Roughly 200 million people practice Tai Chi today, and that number is growing as more people discover the effectiveness of its low-impact, low stress movement. There are five different types of Tai Chi, Chen-style, Yang-style, Wu- or Wu (Hao)-style, Wu-style and Sun-style. It is usually thought of in conjunction with Qi Gong, which has been called the “grammar” of Tai Chi due to its focus on tiny movements.

The ancient martial art Tai Chi, long a means of gentle, meditative exercise, is riding a recent wave of popularity by physical therapists and other individuals interested in using it to rehabilitate injuries and promote health. Tai Chi, which has roots dating back to 13th century China, has been the most popular health regimen to keep an aging population healthy in China, as it requires no special equipment and can be done almost anywhere. Roughly 200 million people practice Tai Chi today, and that number is growing as more people discover the effectiveness of its low-impact, low stress movement. There are five different types of Tai Chi, Chen-style, Yang-style, Wu- or Wu (Hao)-style, Wu-style and Sun-style. It is usually thought of in conjunction with Qi Gong, which has been called the “grammar” of Tai Chi due to its focus on tiny movements.

Tai Chi is being used to help heal sports injuries, such as shoulder separation, knee strains and is among other low-impact exercises for ball of foot pain. There isn’t much clinical research being done to quantify its effectiveness, but most physical therapists, personal trainers and sports physicians have collected anecdotal evidence of its success in helping injuries heal. Approximately three million people in the US are now practicing Tai Chi, giving rise to a new interest in researching its benefits. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health is currently supporting research on Tai Chi’s effectiveness on bone health, osteoarthritis of the knee, cancer survivors, chronic heart disease, and depression. At Harvard Medical School, Catherine Kerr, an instructor who studies the effects of exercise on the brain and body and has practiced Tai Chi for fifteen years, is careful to note that the research is still in its infancy. The outlook is promising. Noting that Tai Chi is especially interesting because it combines a complex memorized sequence of movements with low-impact aerobic exercise, Kerr points to other studies of related elements such as meditation, motor skills, and focus that have been shown to actually change the structure of the brain as well as being associated with training-related changes in specific areas of the brain.

There has been some significant research around the effectiveness of Tai Chi in helping older individuals prevent falls and maintain balance, which is especially important considering that fall-related injuries are the leading cause of injury-related death among the elderly. Tai Chi movements focus on shifting balance from one leg to another while coordinating with movements of the upper body. The continual shifting of body weight appears to give practitioners increased proprioception –the unconscious ability to recognize where their bodies are in space– and to react in the event of a disturbance or impending fall by “catching” themselves.

In one study comparing men over the age of 65 with at least ten years experience doing Tai Chi (and no other form of exercise) against a group of sedentary men, it was found that the Tai Chi practitioners scored better on tests of flexibility, cardiovascular function and balance. Another study, which focused on individuals with mild balance disorders, found that after eight weeks of Tai Chi training, significant improvement in performance on a standard balance test was noted. Researchers also found that Tai Chi decreases fear of falling and increases self-confidence in those who practice who are over the age of 70; fully 54% of those studied cited improved balance as the reason for their increased self-confidence. This self-confidence appears to be correlated with motivation to continue exercising, long viewed as a key factor in maintaining health among the elderly.

In one study comparing men over the age of 65 with at least ten years experience doing Tai Chi (and no other form of exercise) against a group of sedentary men, it was found that the Tai Chi practitioners scored better on tests of flexibility, cardiovascular function and balance. Another study, which focused on individuals with mild balance disorders, found that after eight weeks of Tai Chi training, significant improvement in performance on a standard balance test was noted. Researchers also found that Tai Chi decreases fear of falling and increases self-confidence in those who practice who are over the age of 70; fully 54% of those studied cited improved balance as the reason for their increased self-confidence. This self-confidence appears to be correlated with motivation to continue exercising, long viewed as a key factor in maintaining health among the elderly.

It’s clear that the ancient Eastern practice of Tai Chi has a lot to offer our Western world in terms of health, longevity and addressing injuries. Even if individuals only perform the physical movements, there is research that points to evidence of increased blood flow, balance, and strength –but the benefits go beyond the physical and include decreased stress levels and better sleep. There are studies that show that Tai Chi has a profound positive effect on levels of depression among practitioners, including a six-week trial conducted at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior that examined the effects of Tai Chi on depression when combined with an antidepressant.

The next time you are sidelined by an injury, be sure to mention Tai Chi to your physician and physical therapist and see if there are ways of incorporating the practice into your healing regimen. Or, if you’d like to increase the odds of not being injured at all, make Tai Chi a regular part of your exercise program.

Using Tai Chi to Promote Health and Heal Injuries • Tai Chi for Well-Being

[…] here to read the […]