Weber’s Law of Just Noticeable Differences can help us understand our perceptions of changes in force against an opponent when practicing Taijiquan (太極拳). Weber’s Law applies to most types of perception, like the perception of different light intensity or duration or wavelength (color), loudness or length or pitch of sounds, and even psychological perceptions like differences in costs for products or services.

In Taijiquan, the major sense that we are training is touch. Pressure on our skin is detected with our mechanoreceptors. There are other skin sensors that can detect an opponent, including thermoreceptors (detecting heat) and hair follicle receptors (detecting movements of our hairs), but the role that these play in most Taijiquan practice is probably negligible.

Proprioception – the sensing of the strength of effort of neighboring parts of one’s body being used in movement – is also very relevant to sensing the interactions with an opponent in Taijiquan. Mechanoreception and proprioception together is much more sensitive (about seven fold) than mechanoreception alone. But since Weber’s Law should apply to both mechanoreception and proprioception, I will only use mechanoreception, which is easier to illustrate, in this article’s examples.

Weber’s Law essentially states that our ability to sense changes (differences in magnitude) in force (pressure) is proportional to the magnitude of the initial stimulus. Thus, the greater the initial force, the greater a change must be in order to be able to perceive that change; using less pressure (practicing softer) would allow practitioners to sense changes in pressure sooner.

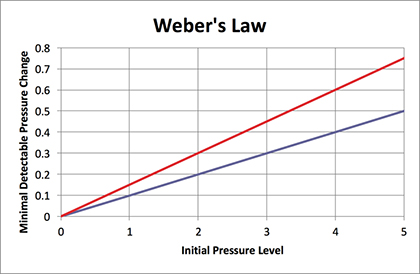

The ability to sense changes in pressure would yield a linear relationship, due to having a constant ratio, which can be plotted as shown in the accompanying graph. The formula would be ∆P/P = k, where ∆P is the minimal detectable change in pressure at pressure level P, and k is the constant. The constant k is, for ease of illustration, arbitrarily set as equal to 0.1 for the blue line in this example, and is 0.15 for the red line (representing someone less sensitive to pressure changes than the person represented by the blue line). [Note that, for an average human, k = 0.14 when measuring pressure on the skin without movement, and k = 0.02 (or 2%) for lifted weights – which includes both mechanoreception and proprioception.]

For this graph, a practitioner (blue) that can sense no less than a 10g pressure change when the initial pressure is 100g, would need a change of 0.1kg when the initial pressure is 1kg, or a 0.2kg difference when the initial pressure is 2kg, etc. The less sensitive participant (red line) would only notice a detectable difference in pressure when there is a 15g change if starting at 100g, 0.15kg change when starting at 1kg, 0.3kg change when starting at 2kg, etc.

For relative comparisons, a golf ball weighs about 45g (0.045 on the X axis of the graph), a baseball weighs about 150g (0.15 on the graph) and a women’s shot put weighs about 4kg (4 on the graph).

Weber’s Law does not always hold for extremes of stimulation, like near the limit of a practitioner’s ability to sense pressure (values close to zero on the graph), or near the maximum that their receptors can sense. If there is no pressure, then the mechanoreceptors will be unable to sense anything, but in order to affect an opponent, some force must be present, so this limitation is unlikely to affect our understanding regarding Taijiquan training.

Weber’s Law indicates that practicing Taijiquan softly would allow the sensing of changes in pressure sooner (i.e., smaller pressure changes) than when practicing more forcefully. This applies to both practitioners indicated in the above graph. But it also indicates that the more sensitive participant will be more sensitive over all the levels of force at which the two practice.

If practitioners are focusing on training for improved sensitivity, then they may benefit from practicing softly. The softer one practices, the less change needed before practitioners can feel that change.

Note that Newton’s Third Law of Motion states, in general, that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This law means that one practitioner will have the same amount of pressure at the point(s) of contact as the other participant. One practitioner cannot be softer at the point of contact than the other person. One practitioner could try to lessen the mutual (net) force by easing up, or they could try to increase the force by trying to applying heavier pressure, but whatever level one participant is at, it is the same for the other participant.

Although the amount of force two practitioners have at the point of contact must be the same, one participant could be using less effort to produce that level of force. Effort is related to efficiency, in structure, breathing, even mental anxiety, etc. I suspect that many people incorrectly use the term “force,” when they actually mean “effort.” We want Taijiquan to be as effortless as possible. We seek to feel calm and “comfortable” while practicing.

Leave a Reply