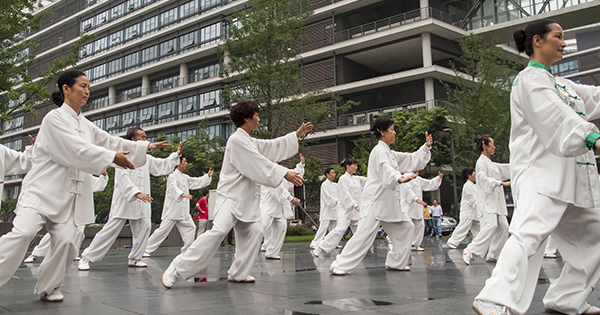

In some respects, stability and mobility counter each other. For example, Taijiquan (太極拳) styles that favour wide or long stances (e.g., Chen 陳 style) have a large base of support, and this can increase the stability in the supported direction, although the waist loses some of its rotational mobility, and stepping would require greater shifting in order to lift a leg. Conversely small styles (e.g., Wu/Hao 武/郝) have a smaller base of support but greater mobility of the waist and can step easier and quicker.

In some respects, stability and mobility counter each other. For example, Taijiquan (太極拳) styles that favour wide or long stances (e.g., Chen 陳 style) have a large base of support, and this can increase the stability in the supported direction, although the waist loses some of its rotational mobility, and stepping would require greater shifting in order to lift a leg. Conversely small styles (e.g., Wu/Hao 武/郝) have a smaller base of support but greater mobility of the waist and can step easier and quicker.

Both of these are desirable, though which predominates depends on the specifics of a situation. We want to have looseness (fangsong 放松) in the joints so that we retain freedom of movement [mobility] in response to pressures, but we also want to retain our balance [stability] and do not want to sacrifice our ability to “root” forces through our structure, which may be compromised if we are too loose (we need to retain muscle tonus and alignment).

There have been clinical studies on stability improvements using Taijiquan to prevent falls and other difficulties in elderly populations. But how does Taijiquan balance stability with mobility in fit practitioners? If used as a martial art, Taijiquan requires both stability and mobility.

A treatment system for elderly patients called Moving for Better Balance® modifies Taijiquan-based movements in their program, as noted in the following slide presentation:

https://www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/Tai-Chi-Moving-for-Better-Balance-1.pdf

I consider balancing stability with mobility as one of the yin/yang (阴/阳) dualities of Taijiquan. We want mobility to complement stability, and vice versa, rather than inhibiting each other. We do not want to resist or brace in order to maintain stability, and we do not want to run away or collapse in order to maintain our mobility.

Mobility, as discussed in this article, refers to both the range of uninhibited movement around joints and the ability to step freely, both even while under pressure from a training partner or opponent. Stability is the ability to maintain or control joint movement or position and to maintain ones balance even while under pressure from a partner/opponent.

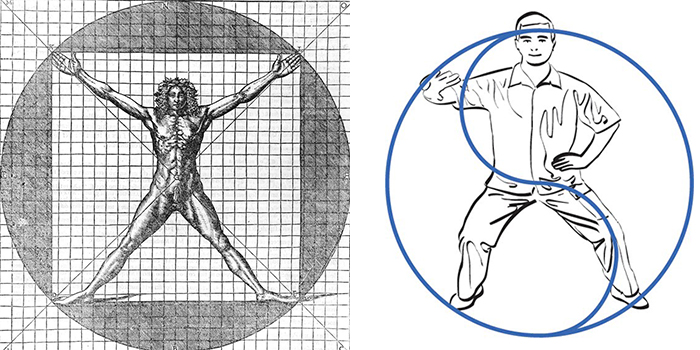

Stability and mobility can be viewed in terms of the square (fang 方) and the circle (yuan 圓). The circle provides mobility (like a ball that can easily roll around) and the square provides stability (like a cube whose large base provides solidity). We are directed to find the square within the circle and the circle in the square (方中有圓,圓中有方 fang zhong you yuan, yuan zhong you fang).

This principle means that when we take a posture to enhance our stability, we should be mindful of retaining our mobility and, when we emphasize mobility, we should still maintain stability. We should be stabile without being stiff or locked in position. Likewise, we should seek stability when moving freely, including when we move into one leg stances or while stepping.

This principle means that when we take a posture to enhance our stability, we should be mindful of retaining our mobility and, when we emphasize mobility, we should still maintain stability. We should be stabile without being stiff or locked in position. Likewise, we should seek stability when moving freely, including when we move into one leg stances or while stepping.

Taijiquan puts an emphasis on roundness since a spherical shape maintains its center and its balance regardless of how it turns or moves. Roundness allows for smooth transitions and quick directional changes. Like a ball floating on water, the ability to rotate and to move is unimpeded, and this trait is very advantageous for defensive actions. But it would be difficult for this ball to issue energy since it lacks the stability of the square.

We typically use the ground as our base of support (our “root”), and we mostly depend on this base/root to power our body’s movements, especially if using “whole-body power” rather than isolated limbs. The feet can be equated with the square since they are flat against the ground when generating power. A ball only has a small point of contact with the ground, and though it has stability due to its shape, it cannot generate much push against the ground and therefore does not have much capability to produce power.

So, while the circle/mobility is great for defense, the square/stability is important for attacking. We want to be able to issue force while defending (the square within the circle), and we want to maintain our ability to change while issuing force (the circle within the square).

Writing attributed to Yan Banhou (楊班侯) states (Paul Brennan translation with comment in brackets):

“Taiji is round, never abandoning its roundness whether going in or out, up or down, left or right. And Taiji is square, never abandoning its squareness whether going in or out, up or down, left or right. As you roundly exit and enter, or squarely advance and retreat, follow squareness with roundness, and vice versa. Squareness has to do with expanding, roundness with contracting. [Squareness means a directional focus along which you can express your power. Roundness means all-around buoyancy with which you can receive and neutralize the opponent’s power]. The main rule is that you be squared and rounded. After all, could there be anything beyond these things?”

Note that “going in or out, up or down, left or right” essentially means “all directions.” “All directions” is often referred to as “six-direction” force, referring to in/out (吞吐 tuntu or swallow/spit, or absorb/reject, i.e. forward/backward), up/down (浮沉 fuchen or float/sink), and left/right (开合 kaihe or open/close).

Wu Zhiqing (吳志青) stated (Brennan translation) “Consider that with roundness there is freedom of movement, but without squareness there is no solidity to your posture. Moving with squareness leads to stagnancy, for movement that is not rounded is not nimble. Use roundness within squareness to find nimbleness, and use squareness within roundness to seek stability. This is the most important thing in the study of Taiji Boxing.”

This energy would expand in every direction simultaneously. This concept helps practitioners respond to unexpected attacks from any direction and any angle, as well as preventing overextending (or falling short) during applications or forms. There should be an active dynamic between simultaneously absorbing and projecting (like a ball’s surface containing the air inside, while the air pressure is trying to expand).

This energy would expand in every direction simultaneously. This concept helps practitioners respond to unexpected attacks from any direction and any angle, as well as preventing overextending (or falling short) during applications or forms. There should be an active dynamic between simultaneously absorbing and projecting (like a ball’s surface containing the air inside, while the air pressure is trying to expand).

A useful analogy for understanding an and ji is an overstuffed suitcase that is difficult to close due to clothing protruding outside the opening. To close the suitcase, one would need to press down (an) on the top of the suitcase while poking the clothing into the crack (ji) until the suitcase can be closed fully. While an is pressing or pushing against the solid substance of the suitcase, ji would be squeezing into cracks, gaps, or weak places; in this case, the suitcase opening.

A useful analogy for understanding an and ji is an overstuffed suitcase that is difficult to close due to clothing protruding outside the opening. To close the suitcase, one would need to press down (an) on the top of the suitcase while poking the clothing into the crack (ji) until the suitcase can be closed fully. While an is pressing or pushing against the solid substance of the suitcase, ji would be squeezing into cracks, gaps, or weak places; in this case, the suitcase opening. Another way of explaining this is that an would attack the partner/opponent through their dorsal or yang (阳) surfaces, whereas ji would attack them by squeezing past their yang defensive surfaces and into their ventral or yin (阴) surfaces. In the illustration, the yin (ventral) surfaces are depicted with the dark gray and the yang (dorsal) surfaces are white.

Another way of explaining this is that an would attack the partner/opponent through their dorsal or yang (阳) surfaces, whereas ji would attack them by squeezing past their yang defensive surfaces and into their ventral or yin (阴) surfaces. In the illustration, the yin (ventral) surfaces are depicted with the dark gray and the yang (dorsal) surfaces are white.

Some Taijiquan (太極拳) practitioners, especially those who are older or who primarily practice for health, tend to practice as softly as possible. Some instead practice as if moving or “swimming” through molasses. This article presents my understanding of the benefits of practicing Taijiquan as if moving through molasses. This practice can be more than simply moving slowly, benefiting also from using modest “resistance” against movement.

Some Taijiquan (太極拳) practitioners, especially those who are older or who primarily practice for health, tend to practice as softly as possible. Some instead practice as if moving or “swimming” through molasses. This article presents my understanding of the benefits of practicing Taijiquan as if moving through molasses. This practice can be more than simply moving slowly, benefiting also from using modest “resistance” against movement.

Some variants of the form do occasionally deflect or block the opponent’s saber; for example Fu’s movement 4B, a check to the opponent’s wrist, can instead be used to deflect/block the opponent’s blade. Other forms may use the saber to deflect the opponent’s saber (especially against thrusts) in a manner more common to double edged straight sword sparring.

Some variants of the form do occasionally deflect or block the opponent’s saber; for example Fu’s movement 4B, a check to the opponent’s wrist, can instead be used to deflect/block the opponent’s blade. Other forms may use the saber to deflect the opponent’s saber (especially against thrusts) in a manner more common to double edged straight sword sparring.