There are many mental factors that should be considered when practicing Taijiquan (太極拳), and the way that people naturally react mentally can become traps, especially when interacting with a partner or opponent. Addressing the mind is more familiar to many from the Zen mind approach in Japanese martial arts (especially swordsmanship), but Taijiquan also addresses the mind in many ways, although less formally than in Japanese arts.

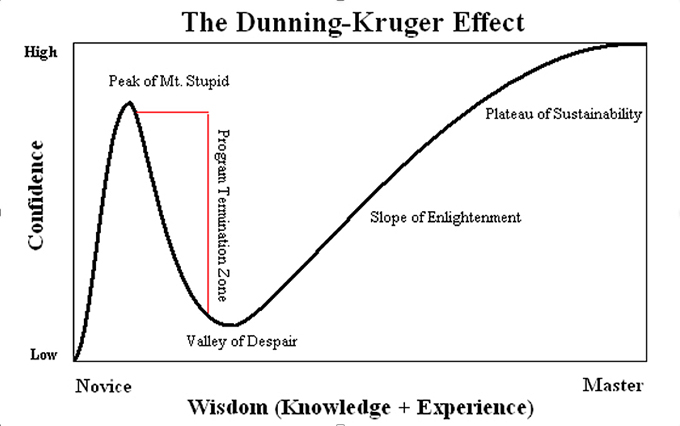

We can start with the tendency of humans to let our egos affect us. For example, people with limited experience tend to think that they are better or more skilled (have higher confidence) in activities than they really are. This phenomenon is called the Dunning-Kruger effect:

https://understandinginnovation.blog/2015/07/03/the-dunning-kruger-effect-in-innovation/

This effect can be described as proceeding from the novice thinking “What?” to “I once was blind and now I see” [“Peak of Mt. Stupid”] to “Hm-m-m, there’s more to this than I thought” [“Program Termination Zone”] to “Oh man, I’m never going to understand it” [“Valley of Despair”] to “OK, it’s starting to make sense” [“Slope of Enlightenment”] and then to “Trust me, it’s complicated” [“Plateau of Sustainability”] as one approaches mastery.

In Taijiquan, novices are often taught to feel their qi (氣energy) flow, or to use intent (用意yongyi), and other concepts that are susceptible to self-delusion (and the Dunning-Kruger effect; the slope up “Mt. Stupid”), especially in the early stages of Taijiquan study. During solo forms practice, there is little feedback available for one to know if they are understanding, and using, the concepts properly. But at higher levels of skill these same concepts (of qi, intent, etc.), once understood, can be very useful.

The effects of ego can often be seen in fights where, after one combatant succeeds in landing a blow, their opponent tries a similar attack back. This is merely one’s ego trying to show that “if you can do something, then so can I.” We should strive to act with what is appropriate to the specific situation, rather than playing “revenge” or “one-upmanship” games.

A similar situation of attempting to show superiority occurs when one side issues force and the other tries to respond with greater force. This leads to force vs. force situations that are contrary to Taijiquan philosophy. Instead, we want to change the situation to our advantage rather than trying to beat the opponent at their own game (where whoever is stronger/bigger is more likely to win). When one lacks the flexibility to change, one often resorts to using more force instead.

Since we were toddlers, we have trained ourselves to lean into, or brace, against force. When first trying to push something, toddlers push themselves away instead, ending in them seated on their diapers. Leaning into the object allows toddlers to use whatever weight they have against the object that they try to push. Our minds have therefore become accustomed to replying to force by applying more force, and to lean or brace when doing so.

But Taijiquan teaches the opposite; to avoid using force against force! We train to issue force from the ground – from our feet, developed by our legs, directed from our waist, expressed in the arms. In push-hands (推手tui shou), interacting like a “butting cow” (顶牛ding niu) is considered to be an error indicative of poor quality Taijiquan. Butting against a partner or opponent reflects our lifetime habit (since we were toddlers) of leaning and bracing, and resisting force with force.

We instead want to “receive” force into our “root” (into the ground). We want to remain comfortable and aligned, and if we conduct incoming forces downward (e.g., by bending our back leg) rather than bracing backwards (e.g., straightening the rear leg), then the incoming force is more aligned with gravity, which healthy human bodies are comfortable with due to naturally “resisting” gravity every time that we stand.

We have habitual mental images of responding horizontally, pushing forward and pulling backwards, instead of pushing/projecting up from, and pulling/absorbing down into, our feet. The horizontal tendency is what produces the “butting cow” posture during push-hands practice. The “butting cow” loses the resiliency of the rear leg which stiffens instead. One would then lose the quality of “loading the spring” (compressing into one’s root – the ground) that is more appropriate for Taijiquan.

When one’s joints stiffen or lock in response to force (either incoming from an opponent, or outgoing from one’s own issuing of force), the body loses its changeability. We may appear stronger (at least in the one direction that the force/resistance is directed towards), but we also become less adaptable. Taijiquan seeks to maintain changeability/adaptability even when under pressure; we want to maintain the openness of our joints, like they are well oiled and free to move, rather than locking/tightening them in place.

Many people when they want to bend lower or raise their leg higher for example, try to use force or momentum to do so rather than trying to relax more. This “try harder” or “do more” approach seems to be what humans have learned to do rather than relaxing (doing less). Unless someone is taught stretching or yoga, or something similar, the tendency is to bounce harder and harder in order to force a greater range of motion.

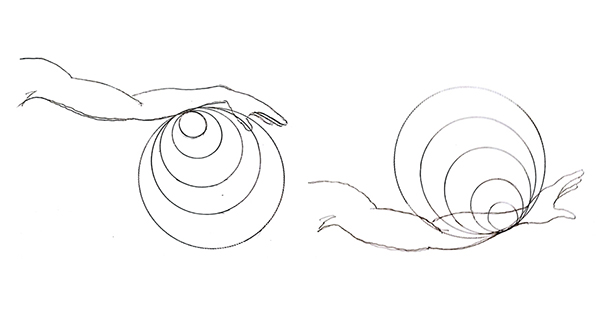

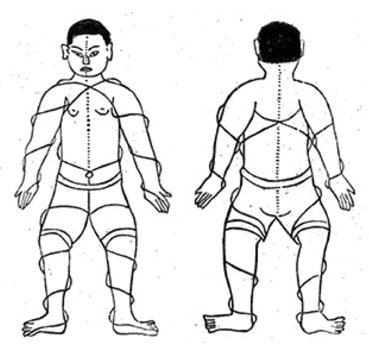

In the accompanying illustration from Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) book, notice how the qi (氣energy) reeling paths wrap around the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. Depending on one’s interpretation of the nine pearl bends, these joints can represent six of the pearls (the other three could be viewed as the lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves in the spine).

In the accompanying illustration from Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) book, notice how the qi (氣energy) reeling paths wrap around the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. Depending on one’s interpretation of the nine pearl bends, these joints can represent six of the pearls (the other three could be viewed as the lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves in the spine). It may help in understanding the concept of the energy cycling around the joints, rather than through the centers of them, if one considers that the muscles that flex or extend the joints go around, rather than through, the joints. In addition to flexion and extension, combinations of muscles allow for rotation, especially in the wrists, ankles, shoulders and hips. Elbows and knees have less mobility and function more like hinges, but the ball joints at the roots of the limbs (the hips and shoulders) do allow for some limited rotation even in the middle of the limbs.

It may help in understanding the concept of the energy cycling around the joints, rather than through the centers of them, if one considers that the muscles that flex or extend the joints go around, rather than through, the joints. In addition to flexion and extension, combinations of muscles allow for rotation, especially in the wrists, ankles, shoulders and hips. Elbows and knees have less mobility and function more like hinges, but the ball joints at the roots of the limbs (the hips and shoulders) do allow for some limited rotation even in the middle of the limbs.

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)?

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)? The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

When we practice from-contact interactions in Taijiquan, we lessen the need for vision to be the dominant information gatherer; we now get much of our information from the sense of touch (e.g., mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors) which often becomes primary. This allows us to relax and soften the eyes, and allow our peripheral vision to increase in importance. Rather than focusing on one or two things, soft focus allows us to take in more information.

When we practice from-contact interactions in Taijiquan, we lessen the need for vision to be the dominant information gatherer; we now get much of our information from the sense of touch (e.g., mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors) which often becomes primary. This allows us to relax and soften the eyes, and allow our peripheral vision to increase in importance. Rather than focusing on one or two things, soft focus allows us to take in more information.

The concept of “four ounces moves a thousand pounds” indicates that size differences should not matter for someone skilled in the art of Taijiquan. Zheng Manqing/Cheng Manching (郑曼青) explains this principle using the analogy of leading a cow by using a cord passing through its nose:

The concept of “four ounces moves a thousand pounds” indicates that size differences should not matter for someone skilled in the art of Taijiquan. Zheng Manqing/Cheng Manching (郑曼青) explains this principle using the analogy of leading a cow by using a cord passing through its nose: