The article “Hypnosis for Tai Chi” is reprinted on Slanted Flying website with the permission of the author Sam Langley from his personal Blog.

Imagine that your Tai Chi skills have improved. You’re ten times better. When people watch you move they are immediately impressed by the fluidity, the grace and the power of your Tai Chi.

Hypnosis has long been used by athletes to boost performance often to great success.

Tiger Woods, Mike Tyson, Andre Agassi, Dorian Yates and Michael Jordan have all used Hypnosis to improve their game and so have many martial artists.

You might be aware of a study done at the University of Chicago by Dr Biasiotto involving Basketball. The subjects were split into 3 groups and tested on how many free throws they could make. The first group practiced shooting free throws for an hour every day, the second group just visualised shooting free throws, and the third group did nothing.

Dr Biasotto tested the participants after 30 days and the results were astonishing. The first group had improved by 24% and the second group, using only visualization had improved by 23%!

Is it possible that Hypnosis can make you better at Tai Chi? I would say it’s highly probable!

Tai Chi is difficult, at least that’s what they say. Maybe viewing it as difficult will make it so. If we change how we perceive our practice there might be a chance we can change it. There’s no doubt that Tai Chi requires dedication and obviously you do need to actually practice. Hypnosis can help you become more motivated to do so.

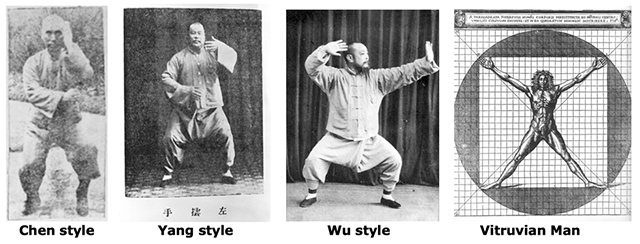

For a while, after one of Master Chen Yingjun’s annual visits, I can often retain a memory of how he moves. When I practice the form I imagine I’m him and I believe it improves the quality of my Tai Chi. You can sometimes experience something vaguely similar just by watching a video.

If you visualize yourself as a master you will gradually move closer to that ideal.

Deep Relaxation is fundamental to Tai Chi and seems to be the biggest stumbling block for most people. I’ve met, seen and pushed hands with many people who had good alignment but weren’t relaxed. If you can become more relaxed mentally you will become more relaxed physically and Hypnosis is a very powerful method for achieving this.

The reason I decided to create a Hypnotherapy session for Tai Chi is that several of my students have asked me how they can become more relaxed. My initial response was ‘Practice more’ but then I remembered that I’m a qualified Hypnotherapist!

It’s not the first time I have combined both practices. I’ve occasionally used simple Hypnosis techniques at the end of my classes. The first time I did so was a light bulb moment.

The good news is that as a Tai Chi practitioner you will have an advantage when it comes to self-hypnosis. You are probably more relaxed than most people and therefore will go into a trance state more easily.

What will happen if you close your eyes and run through the form in your head? Try it now.

Does it feel as though this could be a beneficial practice? Could it conceivably strengthen your mind-body connection?

One thing is sure: It won’t make you any worse and there’s tons of evidence to suggest it will make you a lot better!

Check out the mp3 download available for Hypnosis for Tai Chi!