First the bad news: research indicates that humans are not really capable of multitasking (actively thinking about multiple things simultaneously). However, if some task is routine, then we can focus on another task simultaneously.

When trying to focus on more than one task, we rapidly switch our attention from one task to another. Although it seems instantaneous, switching from one task to another is neither fast nor smooth. There is a significant lag of up to 40% longer than when focusing on a single task, especially when the tasks are complex, or when they use the same type of brain processing.

Research indicates that we may be able to switch focus between two tasks, since our brains are accustomed to either-or (binary) choices. The two frontal lobes of the brain apparently can serial task. One lobe’s task is on hold while the other task is being executed, and this pattern switches back and forth rapidly. But a third task is too much to focus on, and the brain will prefer to drop one task rather than switching between the three.

Research indicates that we may be able to switch focus between two tasks, since our brains are accustomed to either-or (binary) choices. The two frontal lobes of the brain apparently can serial task. One lobe’s task is on hold while the other task is being executed, and this pattern switches back and forth rapidly. But a third task is too much to focus on, and the brain will prefer to drop one task rather than switching between the three.

This system allows us to ignore distractions when we desire to focus on something that we judge to be important. Of course, some people are better at ignoring distractions than others are. People often benefit from meditation to clear the clutter from their minds that distracts them from focusing on current tasks.

Slight of hand magicians use our one-track-mind nature to distract us from what they do not want us to see. They use gestures, choreographed movements, eye contact and facial expressions, a distracting patter of speech – multiple things to catch our eyes and ears and keep our minds off balance. Their success is an indication of how poorly humans focus on multiple things.

When young, many of us have experienced the difficulty of patting our head while simultaneously rubbing our belly, and those people who are especially clumsy are teased with the exaggeration that they cannot walk and chew gum at the same time.

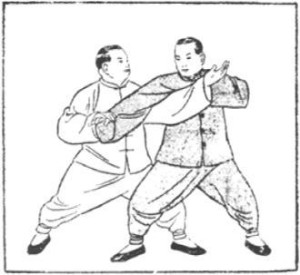

Of course, walking and eating are routine for most people, so we should be able to do these activities simultaneously. But what about martial arts, where the opponent presents us with variable stimuli when interacting with us? Even in controlled freestyle push-hands interactions, we typically need to be aware of what both of their hands are doing, even if the legs are not also allowed to attack us.

Training does help to make tasks familiar enough to focus on other aspects of an interaction. For example, a drummer in an improvisational music group can use both arms and both legs to produce different rhythmic patterns, all while tracking the progressions of the musical piece, as well as listening to what the other musicians are doing, and modifying their drumming to complement the other musicians. Some drummers can even sing while playing (adding melody to their focus on rhythm).

Taijiquan (太極拳) practitioners often start by learning the choreography of a solo form. This is motor learning (“muscle memory”) or learning specific movements through repetition. Eventually, the moves will become familiar enough that less attention needs to be devoted to them, and eventually they can be performed without conscious effort (the movements are stored in the brain as memories). But even after learning the form, practitioners can usually only focus on one or two aspects for refinement during each practice.

Taijiquan solo training is not so different than the following description for dancers:

“Most dancers share a relatively similar path, first learning the choreography and then adding layers of detail and color. Finally, they absorb the work so completely that its elements literally become automatic, leaving the dancer’s brain free to focus on the moment-by-moment nuances of the performance” (Diane Soloway, 5/28/2007).

LEGS – Up/Down:

LEGS – Up/Down:

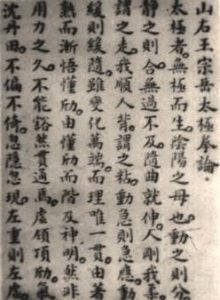

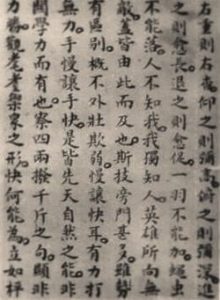

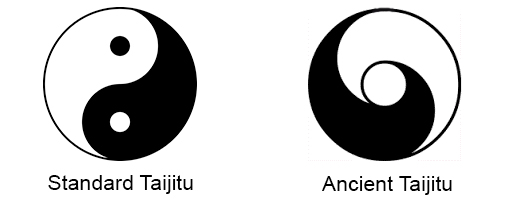

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable.

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable. He is hard while I am soft…

He is hard while I am soft…

n addition to the principles mentioned in the Wikipedia article, I would propose that a major aspect of Taijiquan push-hands is training in the middle range. To transition into fighting with Taijiquan, practitioners may need to practice additional methods not commonly taught in the push-hands format

n addition to the principles mentioned in the Wikipedia article, I would propose that a major aspect of Taijiquan push-hands is training in the middle range. To transition into fighting with Taijiquan, practitioners may need to practice additional methods not commonly taught in the push-hands format