Counter-Point Neutralizing in T’ai Chi Sparring

by David X. Swenson & David Longsdorf

Abstract

T’ai chi sparring often relies on the use of pushes, pulls, and joint twisting (chin na) techniques. There are several points on the body that can be touched, pressed, or hooked to briefly neutralize the power and leverage of such an attack. Counterpoints are unusual because they involve much less effort than the forces they neutralize. This article describes six counterpoints and explores how they may work.

Introduction

T’ai chi sparring, whether slow motion choreography or fast free-fighting, is often described as a fluid dance between partners, in which they attack, neutralize, and counter-attack. Attacks are typically redirected by deflecting the blow or moving with the force, but in some instances a skilled attack prevents such reaction and balance is upset. The use of counterpoints provides a rapid response to pushes, pulls, and joint twisting techniques, that briefly neutralizes the force. Counterpoints are points on the body of the attacker that, when touched or lightly gripped by the defender, effectively neutralize the force or leverage of the attacker’s technique. This article describes how counterpoints were discovered, describes six of 18 applications that have been developed, and explores several explanations of how they may work.

After practicing solo forms for several years, many t’ai chi practitioners become proficient at the forms, and increasingly curious about how the forms work. They build sensitivity and begin to explore applications through push-hands (tui shou) and then more spontaneous applications in free sparring (san shou). Some masters have made significant contributions to understanding the mechanics, particularly William Chen, who has exhaustively studied the biomechanics of postures, TT. Liang who emphasized the subtlety of applications, and Stuart Olson, Bruce Kumar Frantzis, Pete Starr, and Don Ethan Miller who emphasize variety of applications. It was in this spirit of curiosity that the Duluth T’ai Chi Study Group began exploring the mechanics of forms in a particular version of slow sparring we have been developing over the past 20 years.

To many people, their experience of t’ai chi is limited to seeing the slow-motion series of postures studied in the early stages of training that are used to meditate, learn proper form, relax deeply, develop balance, and coordinate all parts of the body. In later stages of practice, especially partner practice and weapons training, speed is increased while the same principles of good form, relaxation, balance and coordination are maintained. Learning to spar usually progresses from simple push-hand exercises between partners, to moderately paced and precisely choreographed attack-defend exchanges, to very fast and spontaneous free fighting. When the first author (Swenson) suffered a back injury and was unable to continue vigorous sparring but was unwilling to forego sparring altogether, he compromised the fast and slow aspects and began experimenting with slow but spontaneous sparring.

In slow sparring, the partners move at a consistent pace, either slow or moderate pace, and avoid speeding up or changing pace. This is difficult at first because most players want to speed up to deflect the attack; they want to avoid being hit and want to win. However, in t’ai chi, to “invest in losing” helps students better understand where they have been open for attack and how to correct it. Since the slow strikes do not hurt (they lightly touch the opponent), one can spend time in focusing on the principles of movement and understanding the opponent’s movement, not just on continuously defending oneself.

Sparring at a slow but consistent pace reduces the need for partners to speed up, and therefore reduces competitive and aggressive attitude. It also enhances cooperation and mutual learning among students. This is also a helpful experience for instructors who must model humility by being open to being struck or pushed and learning from it. The sparring proceeds slowly, somewhat faster than the solo form, and as applications emerge, the partners can stop, repeat, and analyze the application. This was how we discovered the counterpoints. Instructor Swenson was sparring with senior student Richard Townsend who began to push his chest. Beginning to lose balance, Swenson responsively hooked his thumb on Townsend’s pushing elbow, and the push was immediately and surprisingly neutralized. The technique of neutralizing the push was so effective that Swenson and t’ai chi partner David Longsdorf began searching for more counterpoints. Although we are continuing to explore more applications, we have currently found 18 counterpoints that effectively neutralize the techniques of push, pull, press, and chin na (wrist techniques and locks).

Applications

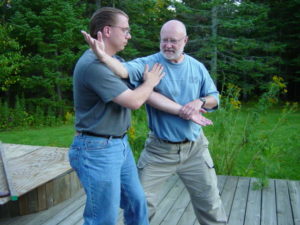

The principle behind counterpoints is that they involve applying a relatively light pressure on a point on the body (usually a joint) that has the effect of neutralizing a very strong pressure (e.g., push, pull, twist, etc.) on another part of the body. To demonstrate this concept, have a partner push on your chest with their right hand (see Fig. 1). At the same time, lightly hook the crook of your right thumb and wrist to their right elbow. Although you do not apply pressure against their elbow, their effort to push you tends to increase the pressure against that elbow point. This light pressure counteracts their push, thereby neutralizing it. The interesting aspect of this technique is that the defender does not need to apply an equal amount of pressure to the elbow that the attacker is applying to the chest. A minor pressure will neutralize a much stronger push.

Figure 1. Elbow counter-point to neutralize single-hand push

We reasoned that if a counterpoint worked effectively to neutralize a push then it might work on a pull as well (see Fig 2.). Have a partner grasp your wrist and pull downward and back in order to break your posture and imbalance you. First try resisting using strength and without using the counterpoint. Usually you will find that you are using a great amount of effort as well as becoming quite stiff, which would enable your opponent to take advantage of this to unbalance you. Next, while your wrist is being pulled back and down, maintain good upright posture but relax, let your arm go slack, and lightly touch the shoulder of the partner with your free hand. This will effectively neutralize the pull.

Figure 2. Shoulder counter-point to neutralize rearward pull

The technique seems to work as well against double-hand push. As your partner pushes against your chest with both hands (see Fig. 3), either place your fingers or palm against the back of the elbows and lightly pull toward yourself as they push, or place the palms against the front of the elbows and lightly push forward and upward as your partner pushes forward.

Figure 3. Elbow counter-point to neutralize push

Press is a technique unique to the soft arts, and especially applicable to sparring when closing with an opponent. It can be effectively used when one folds the arm from a punch or push into closer proximity to the partner. When your partner begins to press against your forearm and shoulder, lightly touch his shoulder, opposite the pushing hand of the press (see Fig. 4). If the attacker pursues the press while being neutralized by this counterpoint, he loses balance and the press is significantly diminished.

Figure 4. Shoulder counter-point to neutralize a press

The splitting technique of diagonal flying can be used to block a strike or single hand push and then upset the opponent over your leg into a throw. The defender can counter this by touching the attacker’s upper shoulder (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Shoulder counter-point to neutralize diagonal flying

Even chin na techniques appear to have some counterpoint applications. In response to the wrist turning technique (see Fig 6.), the defender is usually turned to the side, breaking posture, and being thrown to the ground. Resisting the turn only results in significant wrist pain and eventually moving with the throw. Using counterpoints we have found that the pressure and leverage of the throw can be largely neutralized. In the figure, notice how the defender’s arm rises into ward-off posture. The ward-off lightly presses against both wrists of the attacker.

Figure 6. Ward-off to neutralize lateral wrist chin-na

Mechanics of Counterpoints

There have been several attempts to explain how counter-points work, especially since the amount of effort applied by the defender appears much less than that applied by the attacker. Many t’ai chi practitioners are comfortable simply saying that it is accomplished by using “neutralizing energy.” While that may or may not be true, we have been interested in understanding the biomechanics of this interesting technique. We have considered misdirection, suggestion, counterforce, and motor circuits as possible explanations, and we have explored these with other martial artists, physical therapists, and exercise physiologists.

A common demonstration of ch’i at tournaments and conferences is to have three to five people in a line push against a single t’ai chi player. The demonstration looks impressive and even comical in that the line of people make no progress in pushing the player back; one would expect five people to easily overpower one person. On careful examination however, it can usually be seen that the t’ai chi player uses misdirection by having the line of pushers slightly redirect the push into his leg to root more strongly, while at the same time he slightly uproots the first pusher who is likewise being pushed from the rear by others. The effect of this uproot is to make the first pusher attempt to regain balance, and does so by resisting those pushing from behind. Thus, the t’ai chi player only needs to imbalance the first pusher who then resists those behind him. In principle, a well-placed counter-balance reduces by magnitudes the strength of the push.

It could be argued that expectation and suggestion tends to bias the outcome in a demonstration. There are stories of Cheng Man-Ching who got a new student to jump up and down by tapping on his head, but which elder students knowingly smiled at, saying that it was the student’s exaggeration. Sifu Swenson often uses a demonstration involving a series of subtle suggestions to enable easy pulling down of an outstretched arm– that even worked successfully with Arnold Schwartzenegger many years ago. Naive students, wishing to please a teacher, consciously or unconsciously tend to cooperate, not wishing to embarrass the teacher, or because they too believe in the “power” of the technique. To rule this out, we have tested the technique on a variety of people who neither knew our skill level in the martial arts nor were informed of the outcome expected. The effects of the counterpoints does not seem to be affected by their expectation.

Counterpoints may be explained by the simple idea of a counterforce: that is, a direct force (e.g., push) is countered by an opposing force that is equal to the attacking force. However, the lesser force of the counterpoints suggest that it is not just a direct counterforce. Physical therapists and exercise physiologists who have experienced the technique have suggested that the counterpoint stimulates a motor circuit outside the level of consciousness. It may be that the line of force applied in the counterpoint does not block the force head-on, but disrupts the balance of the person so that effort is reapplied to maintaining attacker’s balance and is therefore taken away from the attack. A related explanation is that the counterpoint does not affect the attacker, but merely helps maintain the balance of the defender.

While these various explanations unfortunately leave us without a decisive explanation of how counterpoints work, the real value is in the asking and exploring of such questions. What is needed is further testing with biometric equipment in which actual force and balance measurements can be assessed while the techniques are being applied.

Counter-counterpoints

As much as we have found counter-points to be interesting and effective, there are counters to counter-points as well. This should not be surprising to most t’ai chi players since the interactive and dynamic nature of t’ai chi is more like an ongoing game of rock-paper-scissors. In sparring, each of the players is sensitive to the maneuver of the partner and moves to adjust to and take advantage of the partner’s attack and posture. Taking the line of thinking that any technique should likely have a counter to it, we explored how counterpoints could be overcome. It did not take long to find that when the attacker found the push neutralized, a circle or spiral could be used by the attacker to push again and overcome the neutralization. This spiral is much like the silk reeling energy technique (chan suu jin) of Chen style t’ai chi.

Finally, we considered that the chan suu jin counter might also be countered. After much more experimenting, we discovered that by the defender following the same spiralling used by the attacker, the attacker’s counter could also be neutralized. The important idea throughout all this discussion of counterpoints is that such neutralization, though temporary, gives the defender a moment to counter with an alternate technique. By learning the counterpoints, t’ai chi players come to a deeper understanding of this complex and subtle art, as well as learn practical skills for application in self defense.

Much of this is reminiscent of the story of the little boy who asked his father how the world is held up– what is the mechanism? The father decisively replied that “an elephant holds up the world.” The curious child thought about the answer awhile, then asked again, “so what holds up the elephant?” The parent, seeing where this was going, quickly said, “it’s elephants all the way down.” In t’ai chi, every technique has a counter, every counter has a counter, and it’s counters all the way down.

Remember to check out our other articles on Tai Chi Training!

The benefits of t’ai chi practice are generally not noticed until after the practitioner has learned the basic forms and can begin to pay attention to other subtleties of the art. The slow pace of doing forms begins to create what is commonly called “muscle memory” but is actually “motor learning” in the brain at both a conscious and unconscious level. It takes hundreds and up a thousand repetitions to develop good motor learning. A fatty myelin sheath wraps the nerves, provides structure, and insulates the nerve for more rapid and efficient transmission of the nerve impulse, just like the insulation of household wiring. The more times a neural circuit is used, the more myelination occurs, and the more accurate, efficient, automatic, and unconscious it becomes.

The benefits of t’ai chi practice are generally not noticed until after the practitioner has learned the basic forms and can begin to pay attention to other subtleties of the art. The slow pace of doing forms begins to create what is commonly called “muscle memory” but is actually “motor learning” in the brain at both a conscious and unconscious level. It takes hundreds and up a thousand repetitions to develop good motor learning. A fatty myelin sheath wraps the nerves, provides structure, and insulates the nerve for more rapid and efficient transmission of the nerve impulse, just like the insulation of household wiring. The more times a neural circuit is used, the more myelination occurs, and the more accurate, efficient, automatic, and unconscious it becomes. The persistent practice of deep relaxation and good postural alignment in forms can have remarkable effects on reducing muscle tension. Master T. T. Liang recounted the story of his visiting a reclusive old master in the Western mountains of Taiwan. The old man was reluctant to accept visitors, but he finally relented and demonstrated the Golden Rooster on One Leg posture and asked Liang to feel the tension in his calf on the standing leg. Liang said that the leg muscles were soft, with only the deep muscle fibers maintaining the man’s posture. The old man laughingly told Liang, that Liang had learned “wood style t’ai chi” (too tense), while he had learned “cotton t’ai chi.”Super Slow Training.

The persistent practice of deep relaxation and good postural alignment in forms can have remarkable effects on reducing muscle tension. Master T. T. Liang recounted the story of his visiting a reclusive old master in the Western mountains of Taiwan. The old man was reluctant to accept visitors, but he finally relented and demonstrated the Golden Rooster on One Leg posture and asked Liang to feel the tension in his calf on the standing leg. Liang said that the leg muscles were soft, with only the deep muscle fibers maintaining the man’s posture. The old man laughingly told Liang, that Liang had learned “wood style t’ai chi” (too tense), while he had learned “cotton t’ai chi.”Super Slow Training. Several years ago, I received a painful back strain and was faced with stopping sparring for quite a while. Instead, I thought it might be interesting to see if free sparring (san shou 散手) might be done slowly and enable me to continue practicing. Our class began to develop slow motion sparring as part of our regular practice routine. Instead of trying to strike the partner, we focused on mindfulness and flow, and merely watched as our hands slowly found openings. Slow sparring enables seeing the patterns of a partner’s movements and strikes, and this allows earlier adapting to the strikes. Such a complementary approach is also helpful when partners are mismatched in size, age, style, or experience. The purpose was not to compete or win, but to participate with the partner and observe how being in the moment would allow more fluid yielding, deflections and entries. It takes persistence to avoid speeding up to “win”, and the t’ai chi adage to “invest in losing” is at the heart of this practice.

Several years ago, I received a painful back strain and was faced with stopping sparring for quite a while. Instead, I thought it might be interesting to see if free sparring (san shou 散手) might be done slowly and enable me to continue practicing. Our class began to develop slow motion sparring as part of our regular practice routine. Instead of trying to strike the partner, we focused on mindfulness and flow, and merely watched as our hands slowly found openings. Slow sparring enables seeing the patterns of a partner’s movements and strikes, and this allows earlier adapting to the strikes. Such a complementary approach is also helpful when partners are mismatched in size, age, style, or experience. The purpose was not to compete or win, but to participate with the partner and observe how being in the moment would allow more fluid yielding, deflections and entries. It takes persistence to avoid speeding up to “win”, and the t’ai chi adage to “invest in losing” is at the heart of this practice.