According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)?

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)?

By maximizing opportunities to gain feedback, elite performers in their fields increase their chances to learn from that feedback. Taijiquan practice begins with relying on the instructions of one’s teacher(s), but the goal is to gain awareness of our bodies such that one’s body becomes a teacher, one’s own body provides feedback. Self-awareness is one reason why Taijiquan is called an “internal” martial art, and the following are examples of levels of awareness.

NOVICES:

Novice practitioners frequently begin learning in a way that is similar to dancers, by learning a choreographed sequence of postures. Some schools require students to meditate prior to the forms instruction in order to clear the students’ minds and reduce their mental distractions. This increases the potential for paying attention to what their bodies are indicating during their physical practice.

Many schools use the concept of feeling qi (氣) or energy flow in the body. This is something that is difficult to visually detect in the teacher, and something that must be felt in oneself. While this practice does direct students to pay attention to their bodies, unfortunately, there are potential pitfalls to sensing qi, especially for novices.

Our minds have a tendency to deceive us, allowing us to sense what we expect or desire to feel. It is difficult to differentiate between what is real and what merely exists due to expectation or desire. Numerous examples of this problem can be found in scientific studies in psychology, where it is extremely difficult to design rigorous and relevant controls.

One example of this phenomenon can be seen in a study that tested if meditation helps reduce stress. The researchers (Creswell et al., 2014, Psychoneuroendocrinology, 4: pp.1-12) compared stress levels of subjects who, after their meditation, took a standard task assessment (the Trier Stress Protocol), designed to be difficult enough to induce high stress. These were compared to similar subjects who took the same test but without the pre-test meditation.

The study design was superior to most similar research in that selection bias was controlled for, as well as having the controls undertaking similar learning processes to the group being taught meditation, except without the meditation component. They also had an objective control for the typical subjective questionnaire, by drawing a blood sample and measuring cortisol levels (a hormone that is elevated in stressful situations).

The results were surprising. The subjective questionnaire results showed that the meditating subjects had a perception of significantly reduced levels of stress after the stressful task that followed meditation, when compared to the control participants, as was expected. But their cortisol levels were actually significantly higher than in the controls! While the mediators FELT that they were less stressed, their levels of stress were actually higher!

Until a practitioner can distinguish actual sensations of qi circulation from imaginary ones, relying on subjective feelings of qi is probably not useful. However, once a practitioner can reliably perceive their qi, then increases or decreases would provide feedback into the quality of their practice.

BEGINNERS:

While self-assessments of qi levels are unreliable, there are numerous physical principles that are easy to observe and can be used for feedback. Correct understanding and application of physical principles will aid in increasing the feelings of qi circulation; but since the physical principles are easier to detect, they may be better for feedback in beginners than the potentially unreliable feelings of qi.

Various physical and postural principles are taught while students are learning solo forms, and physical corrections to postures are common long after students complete a form. The feedback from a teacher is valuable, but if students learn and understand the principles, then they can self-correct many errors by checking themselves in a mirror. These physical/postural principles are typically noticeable to students, if they know what to look for.

UNDERSTANDING ONESELF:

The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

Knowing Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements , and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. oneself involves synthesizing the various individual components into one whole. It is like the difference between a spider making individual threads of a web, and the completed web where the spider can sit in the center and be able to sense the entire web simultaneously. Understanding ourselves is the stage where we achieve wholeness or oneness, rather than having to think about individual pieces.

At this stage, physical corrections may become too subtle to detect visually, so another method of receiving feedback becomes necessary. For those who can now reliably sense their qi flow, this can be used for feedback. Like an undisturbed spider web, one should feel correct and be comfortably aligned. When the “web” is disturbed by errors, then ones attention should be directed to the problem area.

Since this stage relies on self-evaluation, one’s ego can interfere with making objective evaluations of one’s abilities. It is human nature to think we are better than we really are. Often, postural habits feel comfortable, but these could contain errors that one may not be aware of. “Comfortable” does not necessarily mean correct, and one must be objective in evaluating whether or not one is actually incorporating proper Taijiquan postural and energetic principles. Care should be taken since incorrect habits can often feel more comfortable than correct practice.

To obtain more objective feedback, one can focus on interactive work, where a training partner or opponent provides challenges to ones posture and movement.

Continue to page 2…

The closest you’ll get to not doing is meditating. Of course, once you try to sit there and do nothing you find it’s impossible! You try to calm your mind and it gets busier…..so stop trying and just relax. This is isn’t that easy. How many people do you know that are capable of sitting on a train without looking at their phone? Imagine how it would feel to be happy just sitting there unoccupied.

The closest you’ll get to not doing is meditating. Of course, once you try to sit there and do nothing you find it’s impossible! You try to calm your mind and it gets busier…..so stop trying and just relax. This is isn’t that easy. How many people do you know that are capable of sitting on a train without looking at their phone? Imagine how it would feel to be happy just sitting there unoccupied.

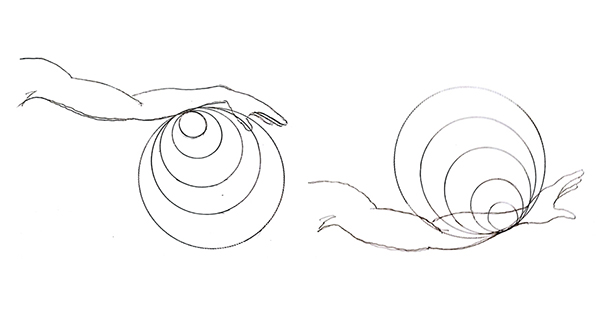

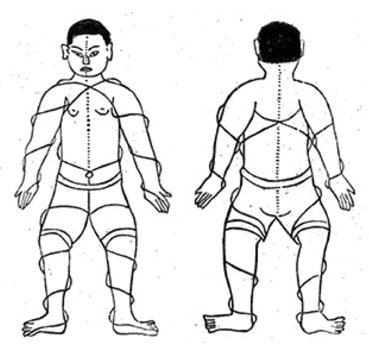

In the accompanying illustration from Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) book, notice how the qi (氣energy) reeling paths wrap around the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. Depending on one’s interpretation of the nine pearl bends, these joints can represent six of the pearls (the other three could be viewed as the lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves in the spine).

In the accompanying illustration from Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) book, notice how the qi (氣energy) reeling paths wrap around the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. Depending on one’s interpretation of the nine pearl bends, these joints can represent six of the pearls (the other three could be viewed as the lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves in the spine). It may help in understanding the concept of the energy cycling around the joints, rather than through the centers of them, if one considers that the muscles that flex or extend the joints go around, rather than through, the joints. In addition to flexion and extension, combinations of muscles allow for rotation, especially in the wrists, ankles, shoulders and hips. Elbows and knees have less mobility and function more like hinges, but the ball joints at the roots of the limbs (the hips and shoulders) do allow for some limited rotation even in the middle of the limbs.

It may help in understanding the concept of the energy cycling around the joints, rather than through the centers of them, if one considers that the muscles that flex or extend the joints go around, rather than through, the joints. In addition to flexion and extension, combinations of muscles allow for rotation, especially in the wrists, ankles, shoulders and hips. Elbows and knees have less mobility and function more like hinges, but the ball joints at the roots of the limbs (the hips and shoulders) do allow for some limited rotation even in the middle of the limbs.

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)?

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)? The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

When we practice from-contact interactions in Taijiquan, we lessen the need for vision to be the dominant information gatherer; we now get much of our information from the sense of touch (e.g., mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors) which often becomes primary. This allows us to relax and soften the eyes, and allow our peripheral vision to increase in importance. Rather than focusing on one or two things, soft focus allows us to take in more information.

When we practice from-contact interactions in Taijiquan, we lessen the need for vision to be the dominant information gatherer; we now get much of our information from the sense of touch (e.g., mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors) which often becomes primary. This allows us to relax and soften the eyes, and allow our peripheral vision to increase in importance. Rather than focusing on one or two things, soft focus allows us to take in more information.

Maybe it was when the floorboards shattered that I realised I was in the presence of a warrior. Taijiquan is a battlefield martial art and its original purpose was war. It’s founder Chen Wangting was a general in the army and watching his descendant as his stamp splinters the ground, Master Chen Yingjun looks ready for battle.

Maybe it was when the floorboards shattered that I realised I was in the presence of a warrior. Taijiquan is a battlefield martial art and its original purpose was war. It’s founder Chen Wangting was a general in the army and watching his descendant as his stamp splinters the ground, Master Chen Yingjun looks ready for battle.

As with any seminar, the training that one receives at an event such as this can only be effective if the lessons are practiced afterwards. My colleagues and I have used many of the lessons that we have learned in our continued training together. I know that I still train in the Chen 13 form on my own. I also have been helping out with a children’s taiji class where we the young students are learning this form. The silk reeling and pushing hands techniques that we have worked with are still a part of my training and the taiji group that I am a part of.

As with any seminar, the training that one receives at an event such as this can only be effective if the lessons are practiced afterwards. My colleagues and I have used many of the lessons that we have learned in our continued training together. I know that I still train in the Chen 13 form on my own. I also have been helping out with a children’s taiji class where we the young students are learning this form. The silk reeling and pushing hands techniques that we have worked with are still a part of my training and the taiji group that I am a part of.

The concept of “four ounces moves a thousand pounds” indicates that size differences should not matter for someone skilled in the art of Taijiquan. Zheng Manqing/Cheng Manching (郑曼青) explains this principle using the analogy of leading a cow by using a cord passing through its nose:

The concept of “four ounces moves a thousand pounds” indicates that size differences should not matter for someone skilled in the art of Taijiquan. Zheng Manqing/Cheng Manching (郑曼青) explains this principle using the analogy of leading a cow by using a cord passing through its nose: