Taijiquan (太極拳) practitioners sometimes view yin (阴) and Yang (阳) as two sides of the same coin, and this can seem like an appropriate analogy for yin and yang united as one whole. But an important principle in Taijiquan is to clearly differentiate yin from yang. A coin’s head and tail sides do not really have the ability to differentiate yin from yang. One could designate one side of a coin as heads and the other side as tails based on different markings, but that coin would behave the same as a two headed coin would. If a coin is behaving the same regardless of whether heads or tails is up (or forward…), then yin and yang are not differentiated.

Slide a quarter and a dime across a tabletop so that they collide, and it would not matter which sides (heads or tails) were facing up. The force of the collision merely depends on mass times acceleration (F=ma), the ordinary qualities of the coins.

Taijiquan does not rely, or focus its training philosophy or methods, on strength or speed. Coins only have mass (size or “strength”) and acceleration (speed) when they collide, despite having two differently designated sides (e.g., heads/yang and tails/yin). Because coins cannot have their yin and yang sides behave differently from each other, coins cannot use their different faces in a way that differentiates yin from yang.

To illustrate the separation of yin and yang, a circular disk can be used, but it is easier to use a bicycle gear rather than a coin. The teeth of the bicycle gear engages the chain to transmit the power from the pedals to the rear wheel. If one only pushes down on the pedals, then they are alternating which foot is providing the power by pushing down on first one pedal and then the other. Each foot/leg would be alternating the yang (pushing the pedal down) and yin (relaxing as the pedal continues up), and this would be differentiating yin from yang.

If, however, one is wearing toe clips (attaching the shoes to the pedals), then both the down-stroke and the upstroke can be used to power the bicycle. This would not only be differentiating yin from yang, but would also represent yang (hard) and yin (soft) mutually helping each other (刚柔相济 gang rou xiang ji). Because of the nature of the circular gear, and the cycle that is produced by its rotation, it is both capable of differentiating yin from yang and having them mutually help each other. This cyclical expression of power is desirable for Taijiquan.

While alternating between yin and yang is necessary to propel a bicycle, it is less clear what is required when practicing Taijiquan. For example, how does one clearly differentiate yin from yang while standing with both feet on the ground? Can one have yin and yang mutually helping each other in one’s legs rather than just alternating between yin and yang when one shifts their weight?

Since there are considered to be five bows (五弓 wu gong) in the body capable of producing power, the two legs, the torso/spine, and the two arms, I will address yin and yang clearly differentiating, and mutually helping each other, in these body segments individually.

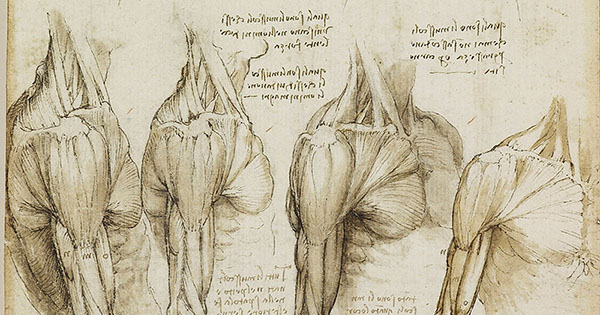

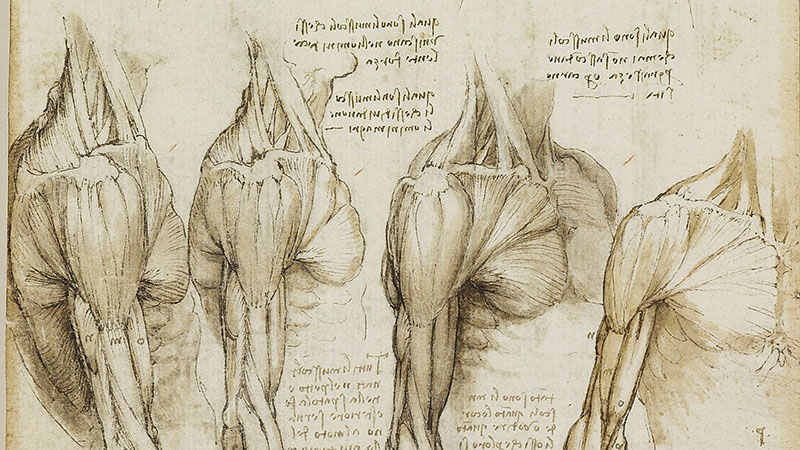

A drawn bow has potential energy stored until the string is released to shoot the arrow. This potential energy is obtained somewhat differently than in one’s body since the material on the outer side of the bow is stretched, and the inner surface material is compressed and, when the string is released, they attempt to regain their original (inherent) shape. So one side of the bow is yang (expanding or pushing) while the other is yin (contracting or pulling). In the legs, the extensor (yang) muscles are on the front of the leg and pull on the bones to extend the leg, whereas the flexor (yin) muscles are on the back of the leg and pull on the bones to bend the leg. But we can still have both yin and yang muscles primed for action simultaneously but without isometric tension (where both flexor and extensor muscles are tensed, and the joint angle is “locked” into an unchanging angle).

The legs push against the ground in order to keep our body from collapsing in response to the force of gravity. This is yang. In order to avoid having just yang in the legs, we are taught to maintain some bend in the knees and avoid locking the legs straight. Additionally, the image of pulling the torso downward, like when lowering oneself into a chair, aids in establishing the potential for having yin (pulling downward energy) in the legs. We want the legs to have a springiness like we have when we jump from standing on a chair and landing on the floor. Landing with the legs just pushing into the floor makes the landing very stiff and could even lead to injury. This is landing with the legs just yang. Likewise, we do not want our legs to be just yin since relaxed legs would not catch us and we would fall to the floor. The way that we naturally learn to land from a jump is the same quality that we want to maintain in our legs while standing.

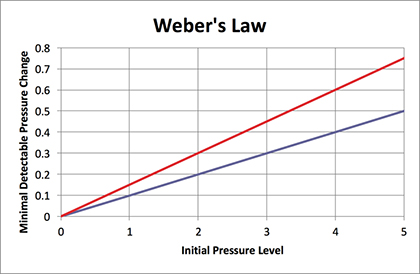

Having both the extensor muscles primed for projecting force (or pushing), and the flexor muscles primed for receiving force (or pulling), simultaneously, is a condition that we want both of our legs to maintain in order to have both yin and yang simultaneously. This can be accomplished by the nature of the stretch reflex. The stretch reflex is an automatic recruitment reflexive action (without the need for conscious commands) that attempts to maintain joint angles. If the joint angle is suddenly changed without the person intending to do so, muscle fibers are automatically recruited to counter that unintended change. This reaction is reflexive and therefore is extremely fast [this is what is seen when a doctor taps the tendon below the knee when checking a patient’s reflexes, resulting in the foot kicking]. The resilience of muscles is also enhanced by their viscoelasticity [viscoelasticity is demonstrated by the classic children’s toy, silly putty, where relatively slow changes allows the material to stretch or act like a “viscous fluid,” whereas sudden changes makes the material bounce or behave like an “elastic solid”].

But humans habitually fail to maintain this yin+yang balance. This can be seen in beginners who alternate between legs when shifting their weight forward or backward, causing them to raise up when straightening (yang) one leg before dropping down when bending (yin) the other leg. To counter this tendency, students are often taught to maintain a constant height (except for a few specific movements) when practicing their forms. Some view the situation where the body is raised because both legs are extended as being “double weighted.” Here the weight is also evenly distributed between the legs, and both are expressing yang (minimal yin) and could correctly be called double weighted. But double weighting can also be viewed as a broader concept and can be applied to what is occurring in a single leg, regardless of one’s weight distribution.

Even experienced practitioners often fail to maintain the yin+yang quality in their legs when engaged in push-hands (推手 tui shou) practice. One often sees them bracing the extended back leg against the ground and exhibiting the undesirable quality like butting cows (顶牛 ding niu). The quality like butting cows is yang+yang and is typically seen in animals where the two back legs push forcefully against the ground in order to propel the body forward to butt against a rival. The back leg(s) then become yang rather than maintaining yang+yin (or yin+yang). If there is no quality of receiving energy (or pulling), then there is minimal yin. Not only are the animals using yang+yang (or double weighting), they are also using force against force, both undesirable qualities in Taijiquan practice.

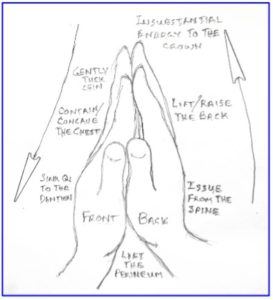

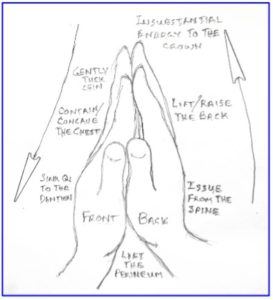

In the torso we want the energy of the back to be yang and expand upwards to the crown of the head. Simultaneously, we want the energy of the front to sink to the pelvic floor. This creates a cycle around the body (matching the “microcosmic orbit” of energy). To illustrate this, one can hold their hands with the palms together (like praying) and push one hand slightly upward to represent the energy of the back rising/expanding (yang) while the other hand sinks down to represent the front of the body sinking (yin). The result is that the “back” lifts simultaneously with the “front” becoming concave, as directed for in Taijiquan literature. This produces the complementary yin+yang cycle in the torso, and this should be maintained in one’s posture whether issuing, or receiving, energy/force.

In the torso we want the energy of the back to be yang and expand upwards to the crown of the head. Simultaneously, we want the energy of the front to sink to the pelvic floor. This creates a cycle around the body (matching the “microcosmic orbit” of energy). To illustrate this, one can hold their hands with the palms together (like praying) and push one hand slightly upward to represent the energy of the back rising/expanding (yang) while the other hand sinks down to represent the front of the body sinking (yin). The result is that the “back” lifts simultaneously with the “front” becoming concave, as directed for in Taijiquan literature. This produces the complementary yin+yang cycle in the torso, and this should be maintained in one’s posture whether issuing, or receiving, energy/force.

We also want to maintain a cycle of energy around our arms. The outer surfaces, with the extensor muscles, are yang while the inner surfaces, with the flexor muscles, are yin. An analogy that illustrates this cyclical quality is how the arms are used when hugging someone. When hugging, one uses their arms to extend (project/yang) around the partner while simultaneously drawing them close (absorbing/yin).

When our arms are maintained in a rounded shape (like in embracing a ball), then we can maintain a cycle of yin+yang around the arms when interacting with an opponent. A properly inflated ball has a spherical shape that maintains a contact point on its periphery with anything that touches it. Additionally, when it rotates in response to the force that impacts it, one side of the ball turns away from the contact point while the opposite side simultaneously moves towards it. Therefore, on one side of the contact point with the ball is yin (turning away) while the opposite side is yang (rotating towards), and therefore the ball maintains yin+yang. We try to maintain this same quality in our rounded arms. If the arms become too angular, then we typically loose this yin+yang quality.

The yin+yang quality in the arms is also facilitated in movement by smoothly transitioning through arcs (partial circles) rather than by reversing directions. Reversals indicate abrupt changes from yin to yang (or yang to yin) and an alternation of the two energies rather than a cycle of the two energies helping each other. Arcs cycle yin and yang energies in a manner similar to pedaling a bicycle while using toe clips. The cycle never stops and never reverses, it just switches from emphasizing yin to yang to yin to yang… as appropriate.

The analogy of the hand stroking a beard addresses this same principle in the hands as was just described for the arms. Contrast this motion with how lobster claws open and close, which is more of an alternation of yin and yang rather than a cycle; claws require a reversal of direction to express different energies. Claws are “double weighted” since both sides are either yin+yin (opening/releasing) or yang+yang (closing/grasping), and are incapable of having yin+yang in how they operate. While this is differentiating yin from yang, claws are incapable of “stroking the beard” cyclical actions.

Throughout our body, we want to have yin and yang clearly differentiated, but it is even better when we can have yang (hard) and yin (soft) mutually helping each other as is done when the energies are maintained cyclically. We seek to eliminate abrupt reversals when changing from one expression of energy to the other. We want to avoid the duality of “fight or flight” and maintain the potential for both yin and yang continuously, while still clearly differentiating yin from yang.

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable.

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable. He is hard while I am soft…

He is hard while I am soft…