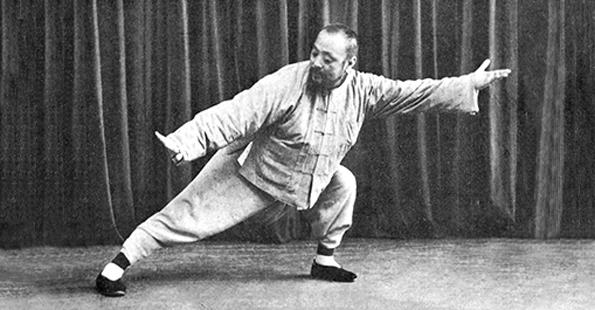

One of the most interesting concepts in Chinese martial arts is the theory of tī dǎ shuāi ná (踢打摔拿). Tàijíquán (太極拳) teachers often overlook this and many times it is only taught by traditional Gōngfu (Kung fu or 功夫) instructors. Few Tàijíquán practitioners have heard this, and fewer still know the true depth of meaning behind the theory.

First, let us examine the meaning of the words. “Tī” refers to leg techniques or kicking, while “dǎ” refers to striking (either open hand or closed). “Shuāi” is the same word found in Shuāi Jiǎo (摔角) or Chinese wrestling, and refers to all wrestling techniques. While “ná” refers to the same word in Qín Ná (擒拿) and refers to grappling and joint locking techniques.

On the surface, this appears to be a way of categorizing the multitude of techniques and application found in Chinese martial arts. While it is true that these categories cover every possible technique employed in hand-to-hand fighting, there is more to this than simply labeling categories. These groupings are arranged to teach a basic and profound logic in how fighting works.

On the surface, this appears to be a way of categorizing the multitude of techniques and application found in Chinese martial arts. While it is true that these categories cover every possible technique employed in hand-to-hand fighting, there is more to this than simply labeling categories. These groupings are arranged to teach a basic and profound logic in how fighting works.

To put it simply, these are the scissors, rock, paper of Chinese martial arts.

To explain this, we will first lump kicking and punching into a single category, which we will call “kickboxing.” Then, we will compare the techniques of three fighters each skilled in a single category of tī and dǎ, shuāi, ná.

The first of our imaginary fighters is only trained kickboxing techniques. Our second martial artist specializes in wrestling, while the third warrior is a master of grappling and joint lock techniques.

For the kickboxer to be effective (barring the use of fā jìn or 發勁 which we will discuss in another article), he must keep his opponent at arm or leg length distance. This range allows each of the kickboxer’s punches or kicks to fully extend and achieve maximum power. If the kickboxer’s opponent is either too close or too far away, our kickboxer’s techniques are useless.

This is where our wrestler comes in.

Wrestlers must get close to their opponents to employ a takedown. Once the opponent is on the ground, the wrestler can employ a hold or submission. Therefore, when our wrestler steps in close to the kickboxer to throw him down, the kickboxer will suddenly discover that his punches and kicks have no power. He will also quickly discover it’s hard to kick or punch your way out of a takedown. Then, once on the ground, the kickboxer’s techniques are useless, while the wrestler has a whole arsenal of techniques with which to hurt or maim the kickboxer. We have seen many real-life examples of this in MMA fighting, when a skilled ground-fighter gets a kickboxer onto the ground.

When the wrestler tries this on the grappler, however, he will quickly find himself in some trouble. The moment the wrestler reaches out to grab our grappler, the wrestler has given both his arms over to his opponent who can then very easily twist a wrist, elbow, or shoulder into a painful grapple.

However, anyone who has studied grappling quickly notices that almost all grapplers have to use both hands on an opponent’s single arm or leg. Therefore, if our grappler tries to put the kickboxer in a painful joint lock, the kickboxer will simply attack the grappler with a free hand (or foot).

Just like scissors, rock, paper, each of these techniques is effective against one of the three, but not the other two. Rock can’t defeat rock, just as it cannot defeat paper. But put rock up against scissors, and it will win every time.

So if the kickboxer is like our metaphorical scissors, our wrestler is the rock (no pun intended), and our grappler is the paper.

Therefore, when you train applications of your Tàijíquán techniques, it’s important to pay attention to each of these categories, developing skills from all three: kickboxing, takedowns, and grappling.

The best way to employ is training is to begin developing applications all three categories for each movement in a Tàijí form. Let us take a traditional long form from Yang-style Tàijíquán (Yángshì Tàijíquán or 楊氏太極拳) as an example. If we remove all the repeated techniques from the form, a list of 108 (give or take depending on who is doing to the counting) the number of unique movements from the form is suddenly whittled down to 37.

The best way to employ is training is to begin developing applications all three categories for each movement in a Tàijí form. Let us take a traditional long form from Yang-style Tàijíquán (Yángshì Tàijíquán or 楊氏太極拳) as an example. If we remove all the repeated techniques from the form, a list of 108 (give or take depending on who is doing to the counting) the number of unique movements from the form is suddenly whittled down to 37.

This means that Yang-style practitioners should be working on all three of those categories with each of the 37 movements. This same math can be used for any other style of Tàijíquán.

Then, to integrate this concept of training into your own practice, start with one or two of your favorite Tàijíquán movement and practice an application from each category until it becomes second nature.

Once you have developed a handful of these, take it to the next level. In a safe pushing hands (tuī shǒu or 推手) environment, practice moving from one technique to the other. Remember to be sure to talk to your training partner so that they are aware of what you wish to emphasize in training (it’s really quite rude to punch someone who’s pushing hands with you if they’re not expecting it). Then, when you can do this effectively while practicing stationary pushing hands, it’s time to integrate these concepts into moving pushing hands training.

It’s important to remember at this point that other basic fighting theories not covered by of tī dǎ shuāi ná must be integrated into training at this level also (perhaps from a Two-person Fighting Set). However, when those basic fighting theories are combined with those of tī dǎ shuāi ná and the principles of moving pushing hands, the result is the highest level of combat training in Tàijíquán, known as “Tàijí sparring.”

Sadly, and particularly here in the United States, I have noticed a huge obstacle to this type of mastery.

Sadly, and particularly here in the United States, I have noticed a huge obstacle to this type of mastery.