If you have practiced Tàijíquán (太極拳) for any length of time, you are sure to have heard a teacher command you to “relax.”

Sometimes they pick on a certain body part by saying things like, “Relax your shoulders!” Other times, they just tell you to relax your whole body.

Why do they do that?

From a martial arts perspective relaxation is essential in the development of proper power. When extending your arm, you have a set of muscles responsible for the “pushing” motion of that arm. You also have a set of muscles responsible for the “pulling” or opposite motion of your arm. In exercise science, these opposing muscle groups are called agonists and antagonists.

It’s important to realize that a strong punch only uses the “pushing” muscles. Because we are extending our arm for the punch, these “pushing” muscles are called the agonists. In order for that punch to be truly powerful, the “pulling” or antagonist muscles must be in a relaxed state.

During martial arts practice a major problem arises because many students mistakenly associate muscular contraction with strength, and think that if they tighten all the muscles (both the agonist and antagonist muscles) of their arm, their punch will be very strong.

When they do that, however, their antagonist or “pulling” muscles are acting against their “pushing” muscles. The result is that heir punch is slower and significantly less powerful.

So when you train your form in slow motion, if you relax all the muscles, except for only the muscles you need to move your arm, your movement will achieve maximum efficiency. Then, when you repeat that movement quickly, you will maintain the quality of your movement and your punch will be very powerful.

The development of power, sometimes called Fā Lì (發力) or Fā Jìn (發勁) in Tàijíquán requires a very specific type of movement which begins in the legs, is given direction by the waist, and then finally expressed in the hands. This, too, requires a certain amount of relaxation to perpetuate the wave of motion.

When watching someone who is very good at Tàijíquán, the Chinese say that the performer’s movements are “liu shuǐ (流水)” or “like flowing water.” This is a direct reference to the wave of movement used in the development of Fā Jìn. Unnatural tension at any point in the chain of muscles used to create this wave will disrupt it, and further inhibit the development of power in Tàijíquán. Thus, a person practicing Tàijíquán for martial arts should relax, or they will not be able to fully realize their power.

In fact, there is actually a risk of practicing Fā Jìn while tense. When this special coordination is trained, the body moves in sequence. The interesting thing is, however, that the muscles involved in this sequence go from large to small. The leg muscles engage to begin the movement. Then the wave of activity transfers from the legs to the large postural muscles of the torso and back, and the legs are allowed to relax a bit. From there, the movement is transmitted to the smaller shoulder and arm muscles. Finally, the movement is handed off to the fingers where it is expressed.

When using Tàijíquán as a martial art, the development of Jìn is an essential part of training. Because these attacks are developed as a kind of wave, from the ground up to the hand, the power moves from the body’s larger muscle groups to the body’s smaller ones. The physics of this is similar to the use of a whip.

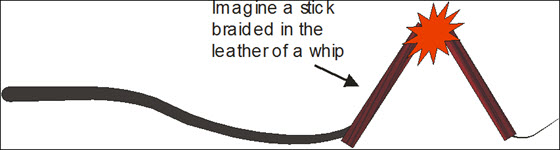

As you see in Figures 1 and 2, when cracking a whip, the power is first developed in the thicker portion, near the handle, and then flows as a wave down the whip to finally be expressed by the tip. The narrowing of the whip actually focuses the power of the strike into a more compact and exponentially more powerful impact.

It takes far more power to swing a bat than to crack a whip. In fact, if you moved a bat up and down with the force necessary to crack a whip and struck something with it, you would barely damage the surface, while the whip’s power is continually focused towards its tip, giving it a deeply penetrating strike.

Tàijíquán is performed slowly and while relaxed—even when studied as a martial art—to help the practitioner develop the proper coordination and timing as well as to keep them form injuring themselves. Once a Tàijí strike is speed up if there is any tension in the body, the energy projected from the wave motion will stop suddenly at the location of tension. Think what would happen if a person braided a stick into the middle of a whip and then cracked it with all his might (see Figure 4). The stick would most likely crack under the pressure of the whip’s motion. The same would happen to whatever structure in the body was tense, which usually constitutes of muscles, ligaments, and tendons.

Now we know why a person practicing Tàijíquán as a martial art should relax, but what about those who practice Tàijíquán for health? Why should they also relax?

For that, we’re going to briefly talk about the process by which Qì (氣) moves through the body. Then, we will examine how Tàijíquán specifically affects this Qì movement, and then we will examine how tension affects that.