A common joke about t’ai chi is about a practitioner who is confronted by a bully to fight. The practitioner agrees to go outside and fight, but tells the bully, “it will have to be in slow motion!” The popular misconception about t’ai chi is that the practice is just a slow motion dance, and many people are surprised that it is also a highly skilled martial art. But what about this slow motion aspect?

Different speeds produce different effects for learning. At fast speeds one can appreciate the momentum of swinging and turning as well as experience the force of strikes, but it is too fast to attend to details and subtleties. Medium speed is perhaps a balance between learning momentum and balance, but still does not provide the detailed attention necessary for exploring nuances of movement.

When moving fast through forms, one set of muscles becomes active to initiate the movement and another stops the movement. Between initiation and stopping there are many other processes occurring, but we move so rapidly we seldom notice them. Slow movement enables us to pay closer attention to relaxing muscles that are not needed for the movement, aligning and sinking the body, relaxing abdominal breathing (we tend to hold it or breathe in the upper chest when concentrating), and linking and coordinating all parts of the body.

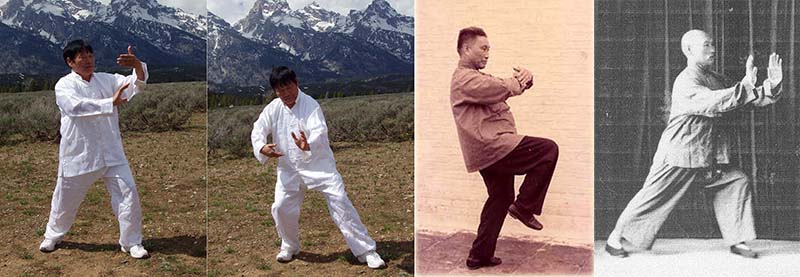

Learning t’ai chi is a complex motor process. Consider the principles of posture from the classics: Keep the head upright, hollow the chest, relax the waist, differentiate substantial and insubstantial, sink the shoulders and drop the elbows, coordinate upper and lower parts of the body, and so on. Each of these requires close attention and practice, let alone how they are all finally integrated into the flowing movements of t’ai chi. Slow and repetitive practice allows attending to each one and gradually integrating them into a fluid form.

The benefits of t’ai chi practice are generally not noticed until after the practitioner has learned the basic forms and can begin to pay attention to other subtleties of the art. The slow pace of doing forms begins to create what is commonly called “muscle memory” but is actually “motor learning” in the brain at both a conscious and unconscious level. It takes hundreds and up a thousand repetitions to develop good motor learning. A fatty myelin sheath wraps the nerves, provides structure, and insulates the nerve for more rapid and efficient transmission of the nerve impulse, just like the insulation of household wiring. The more times a neural circuit is used, the more myelination occurs, and the more accurate, efficient, automatic, and unconscious it becomes.

The benefits of t’ai chi practice are generally not noticed until after the practitioner has learned the basic forms and can begin to pay attention to other subtleties of the art. The slow pace of doing forms begins to create what is commonly called “muscle memory” but is actually “motor learning” in the brain at both a conscious and unconscious level. It takes hundreds and up a thousand repetitions to develop good motor learning. A fatty myelin sheath wraps the nerves, provides structure, and insulates the nerve for more rapid and efficient transmission of the nerve impulse, just like the insulation of household wiring. The more times a neural circuit is used, the more myelination occurs, and the more accurate, efficient, automatic, and unconscious it becomes.

Brain scan studies in 2012 and 2018 of t’ai chi practitioners versus non-practitioners showed that practitioners had a thicker complex of nerve connections in the cortex or covering layer of the brain. They also showed that they had more developed areas of the brain for certain skills such as observation, carrying out motor tasks, sensory awareness of body parts, and integration of emotion and thinking. These findings were greater for practitioners who practiced more and longer over years.

Physical posture is maintained by deeper layers of muscle fibers, called “static fibers”, while movement is executed by phasic or “fast-twitch” fibers. Static fibers work for a long time without tiring and keep us upright and aligned, while phasic fibers can burn out and fatigue. When posture is incorrect, the postural phasic fibers begin to compensate for the fatiguing static fibers. The extra work and tension to maintain posture can interfere with the efficiency of motion. Incorrect fast practice installs movement errors that eventually become unconscious, habitual, and are difficult to reprogram. Consequently, good t’ai chi alignment is relaxed but alert and posture feels effortless and enables agile movements, while tense postures are tiring and easy to uproot.

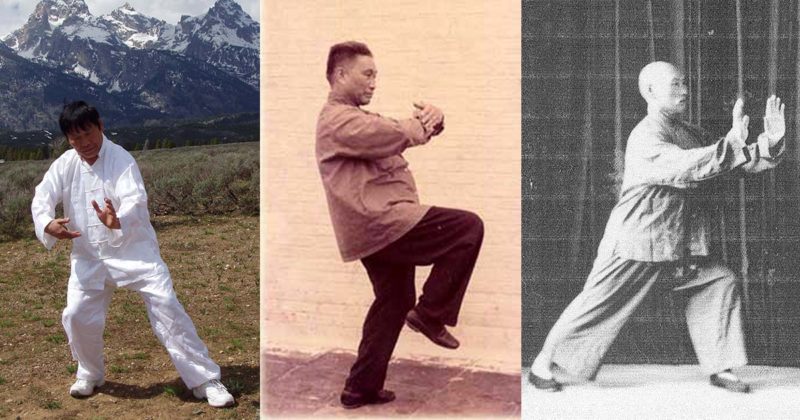

Alignment of the body not only allows for efficient movement and redirecting force, but repetitions in good form also place strain on the skeleton so that calcium is taken into the bones and makes them stronger. Ma Yueh Liang, a physician and prominent master of Wu style t’ai chi, conducted a study of practitioners and found that they had increased bone density along the lines of force developed by good body alignment and movement.

The persistent practice of deep relaxation and good postural alignment in forms can have remarkable effects on reducing muscle tension. Master T. T. Liang recounted the story of his visiting a reclusive old master in the Western mountains of Taiwan. The old man was reluctant to accept visitors, but he finally relented and demonstrated the Golden Rooster on One Leg posture and asked Liang to feel the tension in his calf on the standing leg. Liang said that the leg muscles were soft, with only the deep muscle fibers maintaining the man’s posture. The old man laughingly told Liang, that Liang had learned “wood style t’ai chi” (too tense), while he had learned “cotton t’ai chi.”Super Slow Training.

The persistent practice of deep relaxation and good postural alignment in forms can have remarkable effects on reducing muscle tension. Master T. T. Liang recounted the story of his visiting a reclusive old master in the Western mountains of Taiwan. The old man was reluctant to accept visitors, but he finally relented and demonstrated the Golden Rooster on One Leg posture and asked Liang to feel the tension in his calf on the standing leg. Liang said that the leg muscles were soft, with only the deep muscle fibers maintaining the man’s posture. The old man laughingly told Liang, that Liang had learned “wood style t’ai chi” (too tense), while he had learned “cotton t’ai chi.”Super Slow Training.

World Hall of Fame golfer, Ben Hogan was among the first athletes to promote slow motion practice of his golf swings to analyze in more detail the mechanics of the swing and to train specific muscles for more precise and efficient action. The method is widely used today in golf practice, and other prominent athletes such as Monica Seles in tennis and Jonny Wilkinson in rugby have taken it up. Practitioners take as long as one full minute to execute a single posture. Or as football coach, Tom Martinez says it: “it’s not how fast you can do it; it’s how slow you can do it correctly.”

Ken Hutchins, an inventor and exercise equipment designer, developed the super slow motion strength training method in the early 1990s. He discovered that super slow weight exercise with repetitive movements increased muscle strength faster than rapid movements. The slower the action, the more muscle filaments become activated and cross-connected, and that leads to greater workloads and thus more muscle development. Chen t’ai chi often includes forms with the quan-dao (關刀) (a long-handled broadsword) as part of its regimen, but it tends to be lighter (about 10 lbs) than the heavy training quan-dao of Shaolin that weighs about 40 pounds. The bagua dadao (big knife 大刀) can weigh between 5-10 pounds and is 4-5 feet long– a challenging weapon to swing. Slow motion practice with these large weapons can provide both the benefits of weight training as well as teach rooting, alignment, linking, continuity, and efficiency of movement that are essential in the martial arts.

In the heat of a contest or self-defense, it is easy to become tense, and this in turn tends to produce more tension and anxiety, and reduces deep abdominal breathing. Tension also can interfere with the linking of body segments and development of torque—the “silk reeling” (chan suu jin 纏絲精) emphasized in Chen style. Practicing very slowly and gradually speeding up helps reduce unnecessary tension.

Meditation and Mindfulness

T’ai chi is often described as meditation in motion, and more specifically as mindful meditation. The prominent psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced Me-High Chick-Sent-Me-High), has studied athletes from many sports and coined the term, “flow” for the focused, alert, and unselfconscious state of mind when they are at the peak of their performance. Flow has been described by various athletes as the self and the activity becoming one unit; thoughts move to the background, awareness of body and environment become enhanced (mindfulness), and there is a sense of full participation in the present situation.

The flow experience is strikingly familiar with Chuang Tzu’s story of the Taoist sage, Cook Ting. Ting was butchering an ox for Lord Wen-Hui, who complimented Ting who showed relaxed grace and skill in the cutting. Ting replied, “a mediocre cook changes his knife once a month because he hacks. I have had this knife for 19 years and cut up a thousand oxen, but the blade is just as good as when I got it. Without thinking I find the hollows with my knife and follow things as they are. Then the meat falls away.”The practice of mindfulness has reached faddish proportions in the health literature, but its real benefits should not be overshadowed by pop enthusiasm. Being mindful or “being in the present” is important in martial application as well as for health benefits. Mindfulness is nothing more than being fully aware in the present—not thinking, planning, or trying—just being and participating. While early t’ai chi practice involves paying conscious attention to your posture, direction of your feet, weight distribution, and so on, mindfulness is an openness to the flow of awareness, both internal and external. During forms practice, internal awareness may focus on internal sensations. External awareness may involve noticing sensations such as the colors and forms that come into your direct and peripheral vision, sounds carried to your ears, texture of the ground underfoot, temperature around you, and smells in the air. During sparring, mindfulness may be the awareness of space that you and your partner share in complementary moves but without thinking or planning ahead, or awareness of the slight changes in pressure of touch that signals a push.

In the practice of t’ai chi sparring, thinking ahead of your goals or where to strike can cloud your awareness of the many opportunities that present themselves as you move with your partner. Staying in the moment with your partner results in your push or strike simply moving into the opening unconsciously, often surprising both you and your partner—like water flowing through rocks.

Several years ago, I received a painful back strain and was faced with stopping sparring for quite a while. Instead, I thought it might be interesting to see if free sparring (san shou 散手) might be done slowly and enable me to continue practicing. Our class began to develop slow motion sparring as part of our regular practice routine. Instead of trying to strike the partner, we focused on mindfulness and flow, and merely watched as our hands slowly found openings. Slow sparring enables seeing the patterns of a partner’s movements and strikes, and this allows earlier adapting to the strikes. Such a complementary approach is also helpful when partners are mismatched in size, age, style, or experience. The purpose was not to compete or win, but to participate with the partner and observe how being in the moment would allow more fluid yielding, deflections and entries. It takes persistence to avoid speeding up to “win”, and the t’ai chi adage to “invest in losing” is at the heart of this practice.

Several years ago, I received a painful back strain and was faced with stopping sparring for quite a while. Instead, I thought it might be interesting to see if free sparring (san shou 散手) might be done slowly and enable me to continue practicing. Our class began to develop slow motion sparring as part of our regular practice routine. Instead of trying to strike the partner, we focused on mindfulness and flow, and merely watched as our hands slowly found openings. Slow sparring enables seeing the patterns of a partner’s movements and strikes, and this allows earlier adapting to the strikes. Such a complementary approach is also helpful when partners are mismatched in size, age, style, or experience. The purpose was not to compete or win, but to participate with the partner and observe how being in the moment would allow more fluid yielding, deflections and entries. It takes persistence to avoid speeding up to “win”, and the t’ai chi adage to “invest in losing” is at the heart of this practice.

Slowness and Healing

Injuries, surgeries, and aging can result in changing and limiting the way we move. We increasingly restrict our range of motion and it becomes habitual and feels normal as we become desensitized to body sensation—technically called “sensory motor amnesia.” Fast movement activates these habits of movement and maintains their inefficiency. However, practicing slowly with mindfulness can help identify the sensitive, awkward, and sometimes painful areas and enable working them through.

A variety of studies in the medical literature show slow t’ai chi practice promotes relaxation and reduced stress, enhances immune function, reduces inflammation, decreases pain, improves stability and balance, lowers blood pressure and heart rate, increases range of motion, and provides mild to moderate aerobic intensity. It can also help develop attention, focus and patience as shown in studies with youths with attentional and hyperactivity problems (ADHD). Even brief periods of practice (10 sessions over 5 weeks) have showed improvements in lower anxiety, reduced hyperactivity, less daydreaming, and more appropriate emotions.

Finally, fast self-defense applications are often accompanied by intense and sometimes aggressive emotions. With continued practice, such intense emotions become tied to the forms, rather than calm application that improves self-defense performance. Learning from the beginning with slow forms and calm emotions provides better self-regulation of emotions, both for stress management and self-defense. T’ai chi has been shown to decrease stress levels, depression, anxiety, and enhance emotional stability.

Practicing very slowly is one of the more challenging aspects of martial arts training. In a culture where we like quick fixes, rapid advancement, and fast and powerful actions, slow motion seems counter-intuitive. Yet, this mindful practice is a way to ensure thorough development of the body, mind, and spirit of kung fu.

Remember to check out our other articles on Tai Chi Training!