As a student of martial arts, I have been very fascinated with the internal arts as well as the external arts. Cross training in other arts has been a way for me to learn how I move naturally in a martial art and if it is an art for me. My first foray into the “internal” arts was when I took up Taijiquan around five years ago. Learning Tai Chi has taught me how to move from the inside out, something that has helped me in ways that I cannot explain.

However, when I would train in my other arts, I found myself to be the butt of several jokes. “What’s it like learning to sway to other old people in the park?” I am sure that if you are reading this, you know that which I speak. I remember that one of the first conversations I have ever had with my teacher was the perception of Tai Chi. Also, if you are a reader and practitioner of the art, you know that this is quite far from the reality.

From the training that I have had in Tai Chi, I have done pushing hands and chin na applications. I have left the school with many bumps and bruises over the years, all of which have helped to cultivate my training in such a rich art as Taijiquan. During that time, I have studied and trained in Yang form Tai Chi, sword form, and am getting through Chen form. I have worked on silk reeling, qi gong, brick stability training during those years. During this time, the notion of tai chi being an art where the practitioners move slowly in a serene park becomes a cliché that is further and further from my mind.

I belong to a small, close knit group of Tai Chi practitioners, all of whom are serious about our training (we have the bruises to prove it). One of the ways our Sifu instructs us on our form is to explain the “martial application” of the movement. With movements such as “Snake Creeps Down”, in order to understand the movement, one has to understand how it can be applied in a defensive/offensive manner. While it may be true that some instructors may try to minimize the martial application, our Sifu is quick to explore how it can be used as a way to defend one’s self.

As I continued to explore Tai Chi, my Sifu gave me the opportunity to help teach a class. As is the case in many of my martial arts classes, I make a good person to demonstrate on. As I became the resident “tackling dummy” for several of the classes, the new students he trained, learned that Tai Chi is not an art that is merely “old people in the park”. It is a powerful and legitimate art of self-defense. However, the more that I trained with the new students, the more I started to see the beauty of the art to those who may have health limitations and conditions. I have seen many students come into a Tai Chi class to get a good workout, yet improve their balance, regulate breathing, and work out weakened knees. While I have had friends and fellow students of other martial arts go to the hospital or take time off because of the physical stress that comes along with training in heavy external combat arts, the students who studied Tai Chi would continue to come to class day after day and train in a martial art that did not create as much stress.

To this day, I am constantly picked on for studying an “internal” or “soft” art. However, I see the students (of all ages) who come into the school to learn Tai Chi and am proud to count myself among their numbers. Yes, we may be in the park doing our diligence to express ourselves in the form that we are moving to, but you would do well to treat us with the same respect you would to those doing the external arts such as tae kwon do, karate, judo, etc.

Research indicates that we may be able to switch focus between two tasks, since our brains are accustomed to either-or (binary) choices. The two frontal lobes of the brain apparently can serial task. One lobe’s task is on hold while the other task is being executed, and this pattern switches back and forth rapidly. But a third task is too much to focus on, and the brain will prefer to drop one task rather than switching between the three.

Research indicates that we may be able to switch focus between two tasks, since our brains are accustomed to either-or (binary) choices. The two frontal lobes of the brain apparently can serial task. One lobe’s task is on hold while the other task is being executed, and this pattern switches back and forth rapidly. But a third task is too much to focus on, and the brain will prefer to drop one task rather than switching between the three.

The article

The article

LEGS – Up/Down:

LEGS – Up/Down:

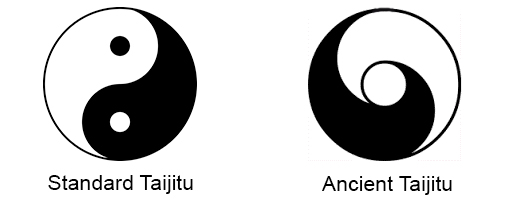

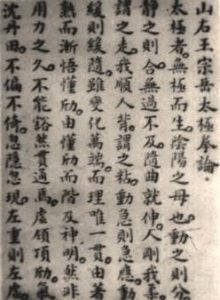

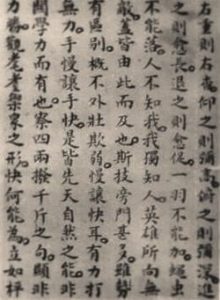

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable.

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable. He is hard while I am soft…

He is hard while I am soft…

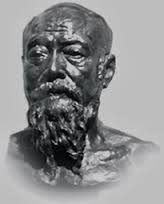

reat Grandmaster Wu Quan You (1834-1902) was the founder of Wu Style Taijiquan and was born in Da Xing County, Beijing. He was a Manchurian and a member of the Imperial Guard in Beijing. He learned Taijiquan from the founder of Yang Style, Master Yang Lu-Chan. Chuan You‘s area of specialization was neutralization. He also studied with Yang Lu Chan’s son, Yang Ban Hou. Through decades of training, he became a very well-known master who had the true skills of Yang Family Taijiquan. Based on the principles of Taijiquan and the influence of studying with Ban Hou, he founded his own style of the art – The Wu Style.

reat Grandmaster Wu Quan You (1834-1902) was the founder of Wu Style Taijiquan and was born in Da Xing County, Beijing. He was a Manchurian and a member of the Imperial Guard in Beijing. He learned Taijiquan from the founder of Yang Style, Master Yang Lu-Chan. Chuan You‘s area of specialization was neutralization. He also studied with Yang Lu Chan’s son, Yang Ban Hou. Through decades of training, he became a very well-known master who had the true skills of Yang Family Taijiquan. Based on the principles of Taijiquan and the influence of studying with Ban Hou, he founded his own style of the art – The Wu Style.