Wu Yu Xiang’s Taijiquan

This article is based on Sun Jian Guo’s book on the Taijiquan of Wu Yu Xiang (1812-1880), and some of it’s components.

In It are included 3 traditional fist forms, an excellent timetable of events, 2 postures from the practice of the training logs situated above the ground, some self-defense applications, biographies of several important boxers and a short lineage chart. Also included is a DVD.

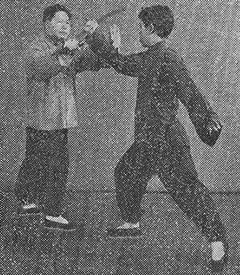

There are photos of Sun Jian Guo (student of Li Jin Fan 1920-1991) with the sword, knife, and staff and also demonstrating Fa Jing (explosive power). Two of his students are posed to begin sparring with knives. These knives are shaped like one half of a spearhead on the dull side of the blade for catching weapons in combat. The author is also shown practicing the staff with a Caucasian student in the mountains, and even Chen Xiao Wang from the Chen family, makes an appearance on page 6.

Also included are certificates, and old manuscripts in this 286-page book, with Sun Jian Guo posing on the cover of the book in a posture from the Wu style 2nd routine called Pao Chui or Cannon Fist.

The author has been frequently featured in Chinese martial arts magazines, and has almost 100 listed students, and his teacher Li Jin Fan, is a direct student of Li Yi Yu’s (1832-1892) student.

The timetable of events as everything else, is written in Chinese, but not the years in which events take place, from 1634-2011.

The 1st routine or form of Wu Yu Xiang was created by him in 1857, and called the center or main form. In 1859 he created Pao Chui, 13 Posture Knife, and 13 Posture sword. Li Yi Yu the prized student of Wu Yu Xiang, is actually the one credited with the creation of the 3rd form simply called “Xiao Jar” (small frame), in the year 1862.

Even for one whose grasp of written Chinese is a foreign subject, the timetable is a fascinating read. Familiar names appear and disappear, associations are seen, and creations of the boxers are born.

Some comparisons of the forms are as follows; the first routine is quite long and the stances are large. All 3 forms begin the same way, but the first form has large stances. The second form has even larger stances than the first, while the third form has small stances.

Each photo is given a number, for example the first routine numbers from 1-374, the second routine 1-159, and the third routine 1-141.

These photographs are large, performed by the author, and beautifully done. There are arrows outlining the movements, and instructions and commentaries. In this one book the author wears 5 different outfits.

There are no jumps or skips in the 3rd form, as there are in the first two. In form 1 posture 159, both feet leave the surface, left hand extended forward with the right hand hidden by the body, right foot higher than the left with the left toes pointing towards the surface, leading up to the movement of striking the opponents groin.

In posture 164-165 of the same form, there is the slapping of the right foot with the right hand, also with both feet in the air.

The jumps in the second routine of Wu Yu Xiang are very pronounced, and when turning the pages of the book, cause one to just stop and look. In posture # 64, the author (demonstrating all 3 forms), looks up into the air, lowers his body, opens his eyes wide, spreads both arms to his sides, before springing into the air into our directional view of 9 o’clock. Both hands are at his left and right sides, similar to athletes giving each other a chest bump.

Video of Sun Jian Guo performing Pao Chui form.

From posture # 72 also in the second routine, from a posture resembling the Yang’s family “Crane Spreads Wings” with the weight mostly on the back left foot with hands forming into fists, the hands switch (left going down and the right coming up) and once again both feet leave the surface looking as if the author is being blown from behind by a very strong wind. The first jump lands in a bow and arrow stance, while the second jump lands in a horse stance.

The second routine is pretty much its own form. Besides the opening and a few postures such as a large “Single Whip”, it bears little resemblance at all to the first routine, although some postures are seen in all 3 forms.

Some variants of the form do occasionally deflect or block the opponent’s saber; for example Fu’s movement 4B, a check to the opponent’s wrist, can instead be used to deflect/block the opponent’s blade. Other forms may use the saber to deflect the opponent’s saber (especially against thrusts) in a manner more common to double edged straight sword sparring.

Some variants of the form do occasionally deflect or block the opponent’s saber; for example Fu’s movement 4B, a check to the opponent’s wrist, can instead be used to deflect/block the opponent’s blade. Other forms may use the saber to deflect the opponent’s saber (especially against thrusts) in a manner more common to double edged straight sword sparring.

Cheng Jin Cai (1953 – 2016) passed away on Sunday, November 6th after a three month battle with pancreatic cancer. He was a 19th generation master of the Chen style of Tai Chi Chuan. Cheng began learning the Chen style of Tai Chi Chuan in 1970 under the guidance of Wang Xian, and continued studying with him until 1973. In 1973 he then began training under the famous 18th generation Chen Family Grand Master Chen Zhao Kui (1928 – 1981). He trained with Chen Zhao Kui until his death in 1983.

Cheng Jin Cai (1953 – 2016) passed away on Sunday, November 6th after a three month battle with pancreatic cancer. He was a 19th generation master of the Chen style of Tai Chi Chuan. Cheng began learning the Chen style of Tai Chi Chuan in 1970 under the guidance of Wang Xian, and continued studying with him until 1973. In 1973 he then began training under the famous 18th generation Chen Family Grand Master Chen Zhao Kui (1928 – 1981). He trained with Chen Zhao Kui until his death in 1983.