In two previous articles I presented unorthodox views of the four primary jin (勁 refined power) of Taijiquan’s (太極拳) thirteen energies/techniques (十三式 shi san shi), peng (掤 rebound), lu (履 divert), ji (挤 squeeze) and an (按 press or push) as they relate to an elastic sphere/ball. Although people are not balls, the energy that we train/develop uses spheres and circles (and spirals, arcs, etc.).

This article presents explanations of the four secondary energies/techniques (corresponding to corner trigrams of the bagua 八卦, eight symbols): 採 cai (grabbing or “plucking”), 挒 lie (applying torque or “splitting”), 肘 zhou (“elbowing”) and 靠 kao (bumping or “shouldering”). Since human bodies are not simple spheres, these four jin give other ways that one can express energy/power.

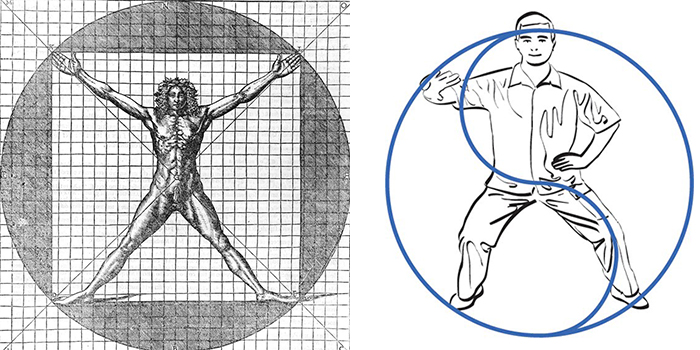

A whole body Taijiquan “sphere” can be viewed like the Vitruvian Man, as one that connects the feet and hands, with the lower dantien (丹田 cinnabar/elixir field, an area inside the abdomen a few inches below the navel) as its center (our center of mass). But since we have joints in ourarms and legs that allow “folding,” we can use sections of our bodies other than our hands and feet (our first sections) to interact with partners/opponents.

Zhou can be viewed as being when we use our elbows or knees (our second sections). Kao can be viewed as being when we use our torso (shoulders, hips, back or chest; our third section). It is similar to having three nested spheres that we can switch between, rather than being a ball with only one surface.

I use bumping for what is often translated as “shouldering” because it better describes this jin that can be applied with any part of the torso. Using the shoulder is the most common, but the hips, back, and chest are all also capable of applying this bumping energy. Additionally, there is nothing inherent in the word kao that refers to a shoulder. Kao translates into English more like “lean on,” “near to,” “adjoining,” etc.

Even though the elbow is specifically referred to for zhou, I view it as actually referring to techniques that use the sphere that includes the knees. Nowhere else in the names of the eight jin are specific attacking physiology like the fingers, palms, fists, shoulders, hips, knees, feet, head, etc. mentioned, and I doubt that such a specific energy as the elbow alone is being referred to here.

While opportunities to use the knee against a partner/opponent’s leg, or to strike their torso with it in a one-leg stance, are not uncommon, it is clearly not as readily available for use, nor as versatile, as the elbow. This is due to the importance of the knee in maintaining one’s stances, and in agile footwork, whereas the elbow is free to be used whenever the range is appropriate.

The “second” and “third” sections of the body can still be used to express the four primary jin (corresponding to cardinal direction bagua trigrams). For example, Chen style has training where partners contact knees (the “second section”) and perform peng, lu, an and ji at the same time that the hands/wrists/forearms cycle through these four jin. Likewise, Wu Gongzao (吳公藻) stated that zhou (elbowing) includes six other energies (e.g., peng zhou, cai zhou, lu zhou and even kao zhou), although he seems to equate the energies more in terms of directions (using the elbow from inside, outside, above, below, or while turning left or right).

We can also use peng, lu, an and ji when contacting a partner/opponent with our torso (the “third” section); being like a mountain that bounces them away (peng), rotating to divert their attacks (lu), attacking partners/opponents by using our torso to press or push against their body or body parts (an), or attacking weaknesses/gaps in their structure (ji).

Elbowing and bumping techniques are also often included in the concept of folding. For example, if the hand is neutralized by one’s partner/opponent, then one can fold (bend) and attack or defend with the elbow, and if that is neutralized one can fold and attack or defend with the shoulder. Of course, unfolding also illustrates this concept of changing the body section being used (e.g. if the elbow is blocked, one can unfold and strike with the fist).

Instead of having one, or three, spheres, we can be viewed as having an infinite number of different size spheres that can interact with partners/opponents. Each elbow or knee can act like a separate sphere, as can our shoulders, hips, back, chest or other places on our bodies. We want to have the energy of an infinite number of spheres at every point of contact with a partner/opponent. Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) boxing treatise states that even the smallest place is circular.

This energy would expand in every direction simultaneously. This concept helps practitioners respond to unexpected attacks from any direction and any angle, as well as preventing overextending (or falling short) during applications or forms. There should be an active dynamic between simultaneously absorbing and projecting (like a ball’s surface containing the air inside, while the air pressure is trying to expand).

This energy would expand in every direction simultaneously. This concept helps practitioners respond to unexpected attacks from any direction and any angle, as well as preventing overextending (or falling short) during applications or forms. There should be an active dynamic between simultaneously absorbing and projecting (like a ball’s surface containing the air inside, while the air pressure is trying to expand).

I have found when used in this way, the extra boost to concentration helps me track orbits and meridians, and the lower dantian sensation is more acute – though maybe that’s just warm tea sitting in my belly!

I have found when used in this way, the extra boost to concentration helps me track orbits and meridians, and the lower dantian sensation is more acute – though maybe that’s just warm tea sitting in my belly!

A useful analogy for understanding an and ji is an overstuffed suitcase that is difficult to close due to clothing protruding outside the opening. To close the suitcase, one would need to press down (an) on the top of the suitcase while poking the clothing into the crack (ji) until the suitcase can be closed fully. While an is pressing or pushing against the solid substance of the suitcase, ji would be squeezing into cracks, gaps, or weak places; in this case, the suitcase opening.

A useful analogy for understanding an and ji is an overstuffed suitcase that is difficult to close due to clothing protruding outside the opening. To close the suitcase, one would need to press down (an) on the top of the suitcase while poking the clothing into the crack (ji) until the suitcase can be closed fully. While an is pressing or pushing against the solid substance of the suitcase, ji would be squeezing into cracks, gaps, or weak places; in this case, the suitcase opening. Another way of explaining this is that an would attack the partner/opponent through their dorsal or yang (阳) surfaces, whereas ji would attack them by squeezing past their yang defensive surfaces and into their ventral or yin (阴) surfaces. In the illustration, the yin (ventral) surfaces are depicted with the dark gray and the yang (dorsal) surfaces are white.

Another way of explaining this is that an would attack the partner/opponent through their dorsal or yang (阳) surfaces, whereas ji would attack them by squeezing past their yang defensive surfaces and into their ventral or yin (阴) surfaces. In the illustration, the yin (ventral) surfaces are depicted with the dark gray and the yang (dorsal) surfaces are white.