Taijiquan (太極拳) practitioners sometimes think of the body as a cylinder, or as a single sphere with the center located at the lower dantien (丹田elixir field; the lower abdomen, the area centered in the waist), but there are numerous spheres that are important to understand. For example, the major joints in the body (i.e., the “nine pearl bends” [九曲珠 jiu qu zhu]) can be considered as spheres with their own centers.

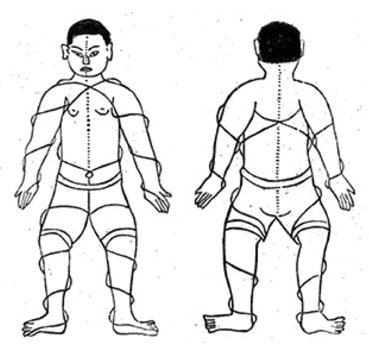

In the accompanying illustration from Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) book, notice how the qi (氣energy) reeling paths wrap around the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. Depending on one’s interpretation of the nine pearl bends, these joints can represent six of the pearls (the other three could be viewed as the lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves in the spine).

In the accompanying illustration from Chen Xin’s (陳鑫) book, notice how the qi (氣energy) reeling paths wrap around the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. Depending on one’s interpretation of the nine pearl bends, these joints can represent six of the pearls (the other three could be viewed as the lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves in the spine).

Practitioners should maintain stable centers in each of these joints, and the qi reeling paths around them can be seen as reflecting the ancient version of the Taijitu (太極圖) shown below.Yin (阴)and yang (阳)energies would cycle around the stabile center circle of the diagram. These individual spheres (pearls/joints) are all contained within the large sphere that is often viewed as having its center located at the dantien and encompassing the entire body.

It may help in understanding the concept of the energy cycling around the joints, rather than through the centers of them, if one considers that the muscles that flex or extend the joints go around, rather than through, the joints. In addition to flexion and extension, combinations of muscles allow for rotation, especially in the wrists, ankles, shoulders and hips. Elbows and knees have less mobility and function more like hinges, but the ball joints at the roots of the limbs (the hips and shoulders) do allow for some limited rotation even in the middle of the limbs.

It may help in understanding the concept of the energy cycling around the joints, rather than through the centers of them, if one considers that the muscles that flex or extend the joints go around, rather than through, the joints. In addition to flexion and extension, combinations of muscles allow for rotation, especially in the wrists, ankles, shoulders and hips. Elbows and knees have less mobility and function more like hinges, but the ball joints at the roots of the limbs (the hips and shoulders) do allow for some limited rotation even in the middle of the limbs.

The lumbar, thoracic and cervical curves/pearls align in an axis that helps establish ones verticality (corresponding to the central dotted lines in Chen’s illustration). It is like three balls, the abdomen, the chest and the head, all stacked on top of each other. This aligns the central axis that would form the center of a cylinder. While the cylinder analogy can be useful when examining one side of the body retreating while the other side advances, it also has limitations.

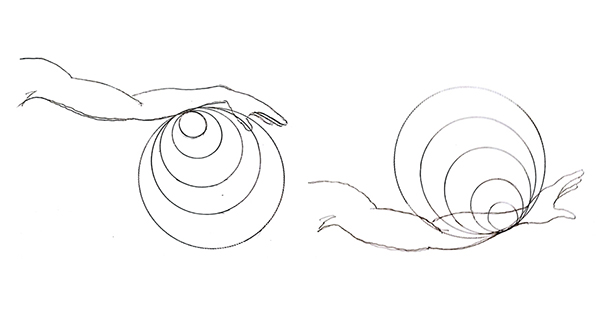

If someone pushes on both sides of a cylinder at the same time (crossing the centerline), then the cylinder can be prevented from rotating and the cylinder will be pushed back. Because of this, each point of contact should instead be considered as being a separate sphere, capable of rotating relatively independently of each other (like the two arms each being capable of relatively independent actions even though each is limited by its attachment to the torso).

There should not be just one body ball/cylinder; there should be multiple spheres (with different centers). A cylinder can be prevented from rotating with two points of contact if they cross the centerline, but a sphere needs three points of contact spread around the center to prevent it from rotating.

While the whole body does make one sphere, there should be an infinite number of possible additional spheres (sometimes referred to as being made up of ball bearings) inside of it. There should be yin and yang on each side of every point of contact (i.e. separate spheres for each point of contact). This takes us into the realm of imaginary spheres, rather than the spheres associated with physical body parts as described for the pearls/joints.

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)?

According to Swedish psychologist K. Anders Erickson, sometimes referred to as the “expert on experts,” those who are the best at what they do are attentive to feedback. Without feedback, how do we know how and when we improve? Many sports have measurable criteria for detecting improvements (e.g., times and distances that are objectively measured), and these can be used as one form of feedback that can help athletes improve. But how do we get the feedback to improve in more personal, and less measurable, endeavors like Taijiquan (太極拳)? The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

The individual physical principles that are learned in Taijiquan cannot all be focused on simultaneously. At best we can focus on one or two at a time (see my earlier article on multitasking), switching from one to another during different practice periods.

The ancient martial art Tai Chi, long a means of gentle, meditative exercise, is riding a recent wave of popularity by physical therapists and other individuals interested in using it to rehabilitate injuries and promote health. Tai Chi, which has roots dating back to 13th century China, has been the most popular health regimen to keep an aging population healthy in China, as it requires no special equipment and can be done almost anywhere. Roughly 200 million people practice Tai Chi today, and that number is growing as more people discover the effectiveness of its low-impact, low stress movement. There are five different types of Tai Chi, Chen-style, Yang-style, Wu- or Wu (Hao)-style, Wu-style and Sun-style. It is usually thought of in conjunction with Qi Gong, which has been called the “grammar” of Tai Chi due to its focus on tiny movements.

The ancient martial art Tai Chi, long a means of gentle, meditative exercise, is riding a recent wave of popularity by physical therapists and other individuals interested in using it to rehabilitate injuries and promote health. Tai Chi, which has roots dating back to 13th century China, has been the most popular health regimen to keep an aging population healthy in China, as it requires no special equipment and can be done almost anywhere. Roughly 200 million people practice Tai Chi today, and that number is growing as more people discover the effectiveness of its low-impact, low stress movement. There are five different types of Tai Chi, Chen-style, Yang-style, Wu- or Wu (Hao)-style, Wu-style and Sun-style. It is usually thought of in conjunction with Qi Gong, which has been called the “grammar” of Tai Chi due to its focus on tiny movements. In one study comparing men over the age of 65 with at least ten years experience doing Tai Chi (and no other form of exercise) against a group of sedentary men, it was found that the Tai Chi practitioners scored better on tests of flexibility, cardiovascular function and balance. Another study, which focused on individuals with mild balance disorders, found that after eight weeks of Tai Chi training, significant improvement in performance on a standard balance test was noted. Researchers also found that Tai Chi decreases fear of falling and increases self-confidence in those who practice who are over the age of 70; fully 54% of those studied cited improved balance as the reason for their increased self-confidence. This self-confidence appears to be correlated with motivation to continue exercising, long viewed as a key factor in maintaining health among the elderly.

In one study comparing men over the age of 65 with at least ten years experience doing Tai Chi (and no other form of exercise) against a group of sedentary men, it was found that the Tai Chi practitioners scored better on tests of flexibility, cardiovascular function and balance. Another study, which focused on individuals with mild balance disorders, found that after eight weeks of Tai Chi training, significant improvement in performance on a standard balance test was noted. Researchers also found that Tai Chi decreases fear of falling and increases self-confidence in those who practice who are over the age of 70; fully 54% of those studied cited improved balance as the reason for their increased self-confidence. This self-confidence appears to be correlated with motivation to continue exercising, long viewed as a key factor in maintaining health among the elderly.