Many Taijiquan (太極拳) practitioners never learn interactive weapons, and some do not even study weaponless interactive principles. This article will introduce some of the benefits of learning interactive weapons, and what those weapons can teach that may not be emphasized in weaponless study.

Each weapon type has unique characteristics that emphasize different aspects of Taijiquan. Although my experience with interactive weapons is somewhat limited, I do have at least some training in all of the five classic weapons of Taijiquan that correspond to the five elements/phases (五行 wuxing) of Chinese philosophy.

In the wuxing, weaponless corresponds to Earth. Practitioners should learn to interact without weapons prior to studying interactive weapons. I will not cover interactive weaponless work specifically, but will point out how the weapons, as I learned them, differ from weaponless work. Weaponless principles should be applied to weapons work.

All weapons will add weight to be controlled, and will improve the connection through the body in order to do so. Practitioners will also need to extend their energy beyond their own body and into the weapon in order to enliven the weapon, and to interact with the opponent through weapons which are less capable of sensitivity than when skin is touching skin. Since stick and adhere, connect and follow (zhan nian lian sui 粘黏連隨) are more difficult through a weapon, practitioners working with weapons will have another vehicle to improve these fundamental skills.

In addition to harmonizing oneself, weapons practice requires that one harmonize with the weapon. It is not easy to smoothly control a foreign object. A weapon has its own center, balance point, and movement characteristics which need to be followed by the practitioner. Holding the weapon creates another joint and/or an extension of the arm.

The creative cycle of the wuxing has Earth producing Metal. Metal corresponds to the saber (刀 dao; knife, single edged sword). Although the saber is not as popular in Taijiquan as the double edged straight sword, according to the wuxing, it should be practiced first after learning weaponless interactive principles.

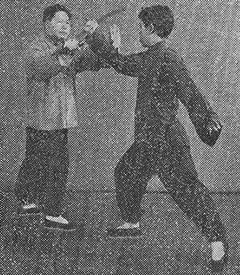

The choreographed sparring form that I learned is very similar to Fu Zhongwen’s version given in the following translation by Paul Brennan:

YANG STYLE TAIJI SABER ACCORDING TO FU ZHONGWEN

The style of saber pictured is called liuyedao (柳葉刀 willow leaf saber) and would traditionally weigh about 1 kg or more (2-3 pounds) and is typically about 36 to 39 inches long. Some Yang and Wu style schools prefer a longer liuyedao blade, and they utilize an “S-shaped” hand guard and a longer handle with a ring pommel. These differences facilitate two-handed techniques. Some practitioners prefer using a niuweidao (牛尾刀 ox-tail saber) instead; a style that developed in the early 1800’s and has a flaring tip (this is the most popular reproduction style and was a folk weapon that was never a part of the official Qing Dynasty weapons inventory).

A saber emphasizes chopping and hacking techniques over thrusting, although thrusts are still possible (depending on the design, some sabers have angled handles to help retain thrusting ability when the curvature of the blade is pronounced). Because of the powerful chopping energy, defense against a saber tends to avoid the blade rather than blocking or deflecting it, and this can be seen in Fu’s sparring form where the saber blades never touch.

Some variants of the form do occasionally deflect or block the opponent’s saber; for example Fu’s movement 4B, a check to the opponent’s wrist, can instead be used to deflect/block the opponent’s blade. Other forms may use the saber to deflect the opponent’s saber (especially against thrusts) in a manner more common to double edged straight sword sparring.

Some variants of the form do occasionally deflect or block the opponent’s saber; for example Fu’s movement 4B, a check to the opponent’s wrist, can instead be used to deflect/block the opponent’s blade. Other forms may use the saber to deflect the opponent’s saber (especially against thrusts) in a manner more common to double edged straight sword sparring.

If you picture facing a chopping saber as being similar to having an axe swung at you, then you can understand why evasion is the primary defense. Dao training therefore emphasizes footwork. Practitioners step to avoid the opponent’s saber, and step again to attack. This means that distance and angles are important features of saber sparring.

When stepping defensively, the saber is often used to strike the opponent’s attacking arm, preventing the opponent from changing directions with their weapon to follow you. This defensive approach (stepping to evade the opponent’s weapon while attacking their arm/wrist) frequently creates openings that allow one to then attack the opponent’s body.

The fierceness of the saber, combined with the emphasis on stepping, reflect the quality associated with this weapon of an enraged tiger charging down a mountain.

The sword (劍 jian) is associated with a flying phoenix or a swimming dragon and, according to the wuxing creative cycle (Metal creates Water) would be the next weapon to learn. Although more difficult to use than the saber, the sword is much more popular for Taijiquan because of the circularity in usage (both dragon and phoenix are said to move in circular, coiling manners). This circularity fits with Taijiquan’s flavor better than the more linear saber usage.

Swords are historically approximately the same length as sabers, but typically weigh slightly less. Personalized measurement for swords and sabers is from the floor to the navel, although some schools prefer longer swords with the length up to the sternum.

I have not been able to find written information online on the interactive sword sparring form that I learned, but the following link from Brennan Translation for Wudang jian gives information about interactive sword:

WUDANG SWORD

This video shows a version of the Taiji jian sparring form that I learned:

Sword usage has more stabbing and cutting than the saber, and teaches lightness and intelligence over power. There is typically deflecting and guiding control over the opponent’s weapon, and the two person drills often look similar to weaponless push-hands drills. The sword is somewhat intermediate between the directness and power of the saber, and the softness of the hand.

Leave a Reply