How the Circle/Sphere Generates and Differentiates Yin and Yang in Taijiquan

An image that I find very useful when teaching interactive Taijiquan (太極拳) is that of a properly inflated ball floating on water.

A ball is an ideal shape since it is spherical and thus responds with circular movements, and the ball floating on water responds instantly to incoming energy. It is balanced and centered, always maintaining a perfect structure with neither protrusions (excesses) nor depressions (deficiencies). It acts only when acted upon, and does not act in opposition to anything, but rather moves with the conditions present in the interaction.

When a ball rotates in response to incoming energy, one side of the point of contact moves away from, while the opposite side moves toward, the point of contact. This generates yin (阴) going away from, and yang (阳) going toward, the point of contact.

The ball is passive, yet practitioners can benefit from emulating the ball when practicing Taijiquan. By actively rotating like the ball, we can create a cycle of energy at the point(s) of contact with an opponent. One side will be yin (retreating, pulling, absorbing, yielding…) while the other side simultaneously is yang (advancing, pushing, projecting, attacking…).

If there is yin on one side of the point(s) of contact with an opponent, and simultaneously there is yang on the other side, then we can avoid the error of “double weighting” (or double pressure). While some schools may have their own preferred way of talking about double weighting, for this article I will define double weighting as having either yin on both sides of the point of contact, or having yang on both sides of the point of contact (i.e., having equal pressure on both sides).

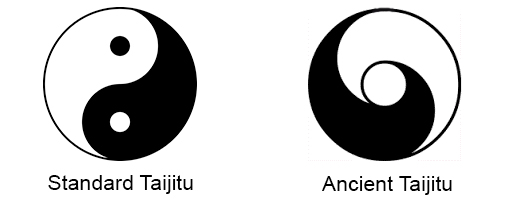

Yin/yin double weighting is collapsing (or running away, limp, etc.) while yang/yang double weighting is resisting (or fighting, tense, etc.). Instead, we want to maintain a condition at the point(s) of contact with an opponent that maintains both yin and yang simultaneously. One can view this as keeping a point of contact on the “s-curve” dividing the yin side from the yang side of the taiji diagram (taijitu 太極圖).

Some schools also use the ancient version of the taiji diagram to illustrate Taijiquan principles. Using this diagram, the point of contact with an opponent would be like the clear center that has the yin and yang cycling around it.

If practitioners clearly differentiate yin from yang around the point of contact, then the amount of contact force can vary from extremely soft to extremely hard, and every level in-between, and the yin/yang balance, interaction and transformations can be maintained.

Many Yang style practitioners train as softly as possible, whereas many Chen style schools practice using significant force. These differences in training are compatible with Taijiquan principles if practitioners understand the separation of yin and yang at the point of contact, and thus realize that both versions can operate somewhere on the “s-curve” of the Taiji diagram.

All practitioners should be able to use Taijiquan against whatever level of force their opponent uses; ideally, using the full spectrum represented by the entire “s-curve” line. The ball floating on water will respond appropriately regardless of whether the contact with it is very light or very forceful.

Leave a Reply