Diǎnxué (點穴, sometimes called Dianmai or even Dim Mak) is known as pressing or sealing the cavity and it is one of the most misunderstood techniques of Chinese martial arts. Most students of Chinese martial arts don’t bother memorizing cavities for striking for innumerable reasons. Knowledgeable teachers are hard to come by, the instruction is boring, precise, tedious, surrounded by myth, mysticism, and obscurity. Not only is finding a teacher difficult, but also finding one who is willing to part with his information is even more challenging.

Before coming to Chinese martial arts, I studied a variety of Korean and Japanese arts. It was in one of these classes that I had my first introduction to the concept of the cavity press. After looking at a poster, which outlined cavities for striking, where it hung in my teacher’s studio, I asked the teacher why he didn’t teach these techniques.

“You need a really strong grip for that,” My teacher replied.

Confused, I asked him to elaborate.

“In a fight, if you’ve grabbed an opponent, you might be able to press a cavity, but you have to be very strong or even that will not work.”

“What about hitting them?” I asked.

“You can’t,” My teacher said simply.

When I asked why you couldn’t hit them, my teacher responded by saying, “Those points are very small. You will never be able to aim with such accuracy. Missing by even a few centimeters means that you have failed to strike the cavity and your attack will be wasted. It’s better to employ more reliable techniques.”

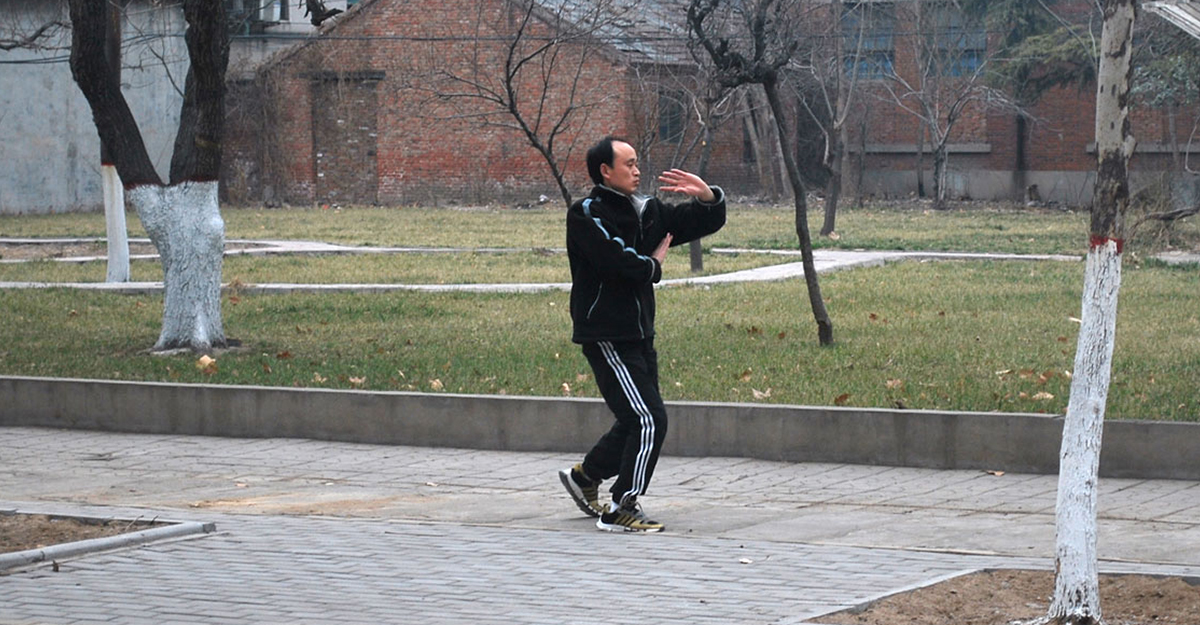

So, from that moment on and for years afterwards, I studied martial arts confident in the knowledge that striking cavities is not a reliable method of fighting. Later, I took up Tàijíquán (太極拳) and about a decade after that, I began to study Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). While in school, learning about acupuncture I suddenly realized that cavity striking one of the greatest weapons in a Tàijíquán practitioner’s arsenal.

So, from that moment on and for years afterwards, I studied martial arts confident in the knowledge that striking cavities is not a reliable method of fighting. Later, I took up Tàijíquán (太極拳) and about a decade after that, I began to study Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). While in school, learning about acupuncture I suddenly realized that cavity striking one of the greatest weapons in a Tàijíquán practitioner’s arsenal.

So, why is it that someone practicing Tàijíquán can strike a cavity with accuracy while a hard-stylist could not?

The answer is simple: external martial arts do not generate power in the same way internal arts do.

One of the most unique aspects of the internal arts is the development of explosive force (Bàofālì 爆發力) known as Fājìn (發勁). The whip-like explosion of movement often seen in Chen-style’s Cannon Fist and New Frame forms are a fine example of this Fājìn power. In pushing hands, a master can apply Fājìn and with a small jerk of his body, the master can send his opponent flying. It bodes the question: how can such a small movement send someone so very far?

Aside from the massive effect of this explosive energy, a Fājìn strike is very penetrative, sending the energy of the strike deep into the body, while an external martial arts strike which uses muscular power or Lì (力), spreads damage out on the surface. Furthermore, a person who has mastered the techniques known as Inch Jìn (Cùnjìn or 寸勁) or Centimeter Jìn (Fēnjìn or 分勁) can strike an opponent with no windup, and the damage done from striking with the fist only an inch or centimeter away from the opponent is just as devastating as punching with a windup. Probably the most famous example of this concept is Bruce Lee’s “one-inch punch,” but in the case of inch and Centimeter Jìn, the fighter will ideally be using Phoenix-eye Fist, focusing all that explosive Fājìn power into a tiny point.

This is Tàijíquán’s secret weapon.

Fājìn actually allows a Tàijí practitioner to find a cavity through touch, and then, without withdrawing one’s hand, the Tàijí practitioner can use Inch or Centimeter Jìn to strike the cavity with amazing force.

As soon as I discovered cavity striking is a viable technique, and I began to examine the recommended striking points found in Chinese martial arts. I quickly discovered that these were the same points I was studying in TCM school.

Of course, not all acupuncture points can be struck effectively, but all the Diǎnxué points were acupuncture points. At that point, I began seeking out colleagues who practiced both Tàijí and TCM with whom I could compare notes. I did this in hopes of finding a way to de-mystify Diǎnxué and to discover why this knowledge was couched in such secrecy.

I found myself asking questions like: “What happens when I strike a cavity? How does that affect the Qì of the human body?”

In order to understand this, we must first understand some basic concepts of TCM. First, it’s important to realize that Qì (氣) is not some mystical and unexplainable energy that wisps around like magic inside the Human body.

The word Qì itself offers a fantastic understanding into its meaning. The character for Qì, 氣, is actually made up of two different Chinese characters. The upper portion of the character, 气 means “air” or “gas.” And there is also the word mǐ (米) meaning “rice.” A saying in Chinese Medicine helps us to further unlock the meaning behind the idea of Qì.

Leave a Reply