Our Qì moves through our body with a circulatory system not unlike the circulatory system for our blood. Like a tree it has thicker “trunks,” which divide into smaller “branches.” The thick “trunks” circulating our Qì are called “meridians,” and their job is to bring Qì to the various organs of the body. In fact, they are often referred to by the name of the organ to which they supply Qì. For example, the Meridian that supplies the heart with Qì is called the Heart Meridian.

There are 12 meridians in all.

They flow from deep in the body near their host organ towards the surface (where the acupuncture points are located and used to promote health of that meridian and organ). They connect with one another both deeply and on the surface forming a chain. It takes a little under 30 minutes for the Qì to start in one meridian and then flow through the whole body.

These meridians also move even further towards the surface, branching into smaller tributaries of Qì, which provide the muscles and tendons with Qì. These are called the “Muscle Regions.” Each muscle region provides the muscles directly above their corresponding meridian with Qì.

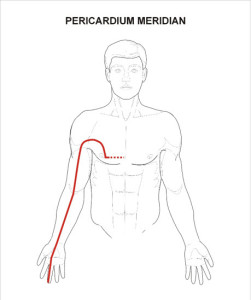

In the Figure 1, we see the pericardium meridian (marked in red), which flows from the structures surrounding the heart into the chest cavity and then moves towards the surface of the body around the shoulder and down the arm to the middle finger.

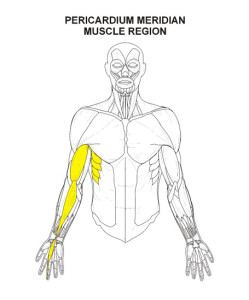

In Figure 2, we see the muscle region associated with the Pericardium Meridian (in yellow). This region branches out from the main trunk of the meridian and supplies Qì to the muscles on the surface. Here we see that the Pericardium Muscle Region supplies many of the forearm flexor muscles as well as the m. biceps brachii with Qì.

When these meridians and muscle regions are healthy, the Qì flows freely and they body functions normally. When they are not functioning, there will be an imbalance of Qì, which can lead to problems along the muscle region, the meridian, or with the organ itself. A trained Chinese doctor can find the location and type of imbalance and then use acupuncture or Chinese herbs to bring the body back into balance and relieve the illness and symptoms caused by the imbalance. Sometimes a Chinese doctor will prescribe Qìgōng or Tàijíquán exorcises for the patient. Qìgōng and Tàijíquán both circulate the Qì through the body helping to restore it to balance.

How then, does this work?

Within Qìgōng, there are two major types of practice. Nèidān (內丹) and Wàidān (外丹). These two types of Qìgōng are categorized based on the way Qì moves through the body during their practices. With Nèidān the Qì is gathered in the deeper tissues and then moved the exterior, and Wàidān builds Qì in the exterior and then moves it to the deeper tissues.

Because it is easy to learn and one can quickly become skilled at it, most people practice Wàidān. One of the main reasons for an ease of learning where Wàidān is concerned comes from the fact that Wàidān practice mimics the natural movement of Qì through our body. When we move around during our day-to-day lives, we are actually moving and gathering Qì.

To explain concept we will examine a statement made by Da Mo in his Yìjīnjīng (易筋經) text. This has been quoted throughout the centuries since then. It is the cornerstone upon which modern Qìgōng and Tàijíquán practices are founded. This saying can even be found repeated in the Tàijí Classic.

The Mind (Yì or 意) guides the Energy (Qì) which activates the muscles (Lì or 力).

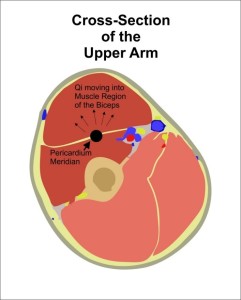

It works like this: if a person wanted to lift weights, doing a bicep curl, they would need Qì to make this possible. They would first desire to move, that would be converted into a thought signal, which would cause Qì to gather in the muscle region supplying Qì to the bicep muscle (the Pericardium Muscle Region). Once enough Qì arrived in the muscle region, the weightlifter would be able to bend their elbow and do a curl.

Like our weightlifter, Wàidān Qìgōng moves the Qì by using muscular contraction to build energy. Wàidān makes use of specific movements and muscular contractions to build vast quantities of Qì in the muscle regions. Then, when the person relaxes, the abundance of Qì they have built up will move deeper into the associated meridian, altering the amount of Qì in the meridian, and affecting the balance of energy all over the body.

Tàijíquán is a form of Wàidān Qìgōng.

To perform a Tàijíquán movement, the Tàijí practitioner must first desire to move. Then this desire is converted into a thought impulse which is sent to the legs. These muscles contract, stepping out to begin the movement. Massive Quantities of Qì are built in the legs and then released, moving into the meridians of the lower leg. The mind then moves to the waist, causing the hips and waist to turn, giving the movement directional force. Qì is gathered in the waist and then released, descending into the meridians of that area. The movement is then passed to the shoulder the elbow and finally to the hand, with the Qì gathering in each location like a wave of energy moving from the feet to the hands.

With each part of the body moving in sequence, the Qì will build in sequence, each muscle group adding more Qì to the wave of energy as it passes from one area of the body to the next. Mental focus during practice, combined with proper breathing (see my article about Qì and cosmology to understand why breathing is so important) will further increase the circulation of Qì during this process.

This raises several questions, however.

For one thing, if we move around all day long, this should circulate the Qì. Why isn’t that enough? Why do we need Tàijí or Qìgōng at that point?

The answer is this: as creatures of habit, we often move unconsciously—without mental focus to help move Qì along. This ensures that only the bare minimum amount of Qì will activate the muscles. Furthermore, muscular contraction consumes energy.

Using your muscles uses up Qì.

And if you are only moving the bare minimum, most of that energy will be used up as you move. Only when we move an abundance of Qì will we see the benefits associated with regular practice of Qìgōng or Tàijíquán.

This is also why relaxation becomes essential. Too much muscular contraction and a Qìgōng practitioner is consuming vast quantities of Qì. This means that the practitioner will not see the benefits of doing Tàijíquán or Qìgōng.

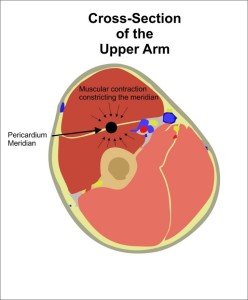

Furthermore, as we see in Figure 9, muscular contraction can compress the meridian, choking off the Qì flow. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, we have a saying, “Where there is pain, there is no free flow. Where there is no free flow, there is pain (Bù tōng zhè tòng, tòng zhè bù tōng, or 不通這痛, 痛則不通).”

This saying means that wherever there is a stagnation of Qì flow, there will be pain in that location. If you hold a weight in your hand, contracting your bicep muscle for an excessively long time, it will begin to hurt. This is because the muscle contraction necessary to hold the heavy weight is starting to bear down on the meridian and stagnate the Qì.

By relaxing during Tàijíquán practice, you will not consume as much Qì, and can therefore build an abundance of Qì with each movement. Furthermore, you will not bear down on the meridians, which can lead to pain associated with your Tàijíquán practice!

Ironically enough, the proper coordination of movement is necessary for both the proper expression of Fā Jìn power as well as the proper circulation of Qì. A truly great Tàijíquán practitioner has a smooth, very subtle wave-like motion, as each muscle “hands off” the wave of power to the next. Those who can do this well will express more power gathering a strong amount of Qì. They are not the same thing, but they are inexorably tied together, and cannot be separated.

Leave a Reply