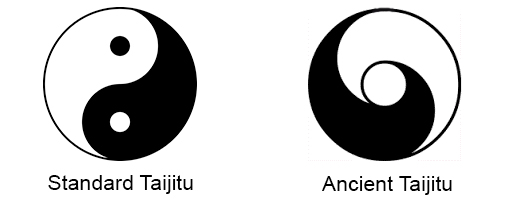

Six-direction force includes the balance of opposing directions for up/down, forward/backward and right/left (阳 yang and 阴 yin pairs), which will be presented in this article. These pairs of directions represent XYZ coordinates, which together represent three dimensional force, the goal being to have energy in all directions like a properly inflated ball.

Zhang Yun wrote an excellent article that includes an explanation of six-direction force in Xingyiquan (形意拳): http://www.ycgf.org/Articles/XY_SanTiShi/XY_SanTiShi.html

While much of what Zhang writes in his article is similar to, or compatible with, Taijiquan (e.g. see “Upward Force” and “Downward Force”), this article will attempt to explain additional aspects of six-direction force in Taijiquan (太極拳) practice.

In action, when one direction of the pair(s) is emphasized, one does not want to lose the counterbalancing opposite direction. Practitioners should maintain some yin in a predominantly yang move, and vise versa. Over-commitment to one direction inhibits the ability to change. When committing to one direction, practitioners should retain the ability to change to any other direction, including the opposite.

LEGS – Up/Down: There are several ways that Taijiquan addresses this principle. One is the rooting into the feet (extending into the earth), while also having the body lifted as if the crown of the head is suspended by a string from above.

LEGS – Up/Down: There are several ways that Taijiquan addresses this principle. One is the rooting into the feet (extending into the earth), while also having the body lifted as if the crown of the head is suspended by a string from above.

If we are standing, then we are producing upward energy (“resisting” the pull of gravity), and this is balanced, in some traditions, by the image that we are pulling ourselves downward as if we are lowering ourselves to sit on a chair.

It is desirable to always have the ability to jump upward and also to suddenly drop downward regardless of where a practitioner is in their form(s). No matter how their weight is distributed in their legs, a practitioner should be able to suddenly raise or lower their body. This action is like a spring. As long as the spring is not fully compressed or fully expanded, it maintains the ability to either compress more or to spring back, depending on the changes in the force acting on the spring.

It is also addressed in some traditions by having the head stay on one level, rather than raising and lowering, while shifting from one leg to the other. By practicing staying level, we are practicing to maintain an up/down balance between the leg muscles that could otherwise be used to raise (using only the extensor muscles) and lower (using only the flexor muscles) our bodies.

LEGS – Forward/Backward: The practice of remaining at a level height when shifting the weight also addresses the forward/backward balance by having us always using one leg to “push” while the other leg “pulls” (rather than pushing with one leg to the apex when both legs are relatively straight, and then collapsing the other leg to continue the movement in that direction).

The balance of forward/backward in the forward advancing leg is addressed by the principle that one should not advance beyond the point where returning/backward energy can be felt. Some address this principle by prohibiting the knee from advancing beyond vertically above the toes. Others are more conservative with the advance restricted to no farther that the center of the foot, or the Bubbling Well (涌泉 yongquan, KD1 acupuncture point). Some even advise going no farther than a vertical shin.

Some practitioners also practice not having the knee extend too far forward when bending the leg by practicing squats facing a wall with the toes touching the base of the wall. In this practice, the thighs should be lowered to horizontal while the knees are restricted from going beyond the toes.

The energy in the rear leg, when retreating, should maintain the ability to spring forward, like a compressing spring. The yin/yang balance of the rear leg, when advancing, is addressed by the requirement to not lock the knee. A locked knee, in any posture, would produce yang without yin, and could make it difficult to change quickly or smoothly.

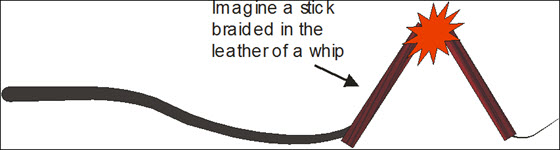

Practitioners used to viewing the legs as being two of the five “bows” (the other three being the two arms and the torso) will have forward/backward (and to some degree up/down) balance similar to a drawn bow. When drawn, a bow will be expanded on the outward (forward, yang) surface while compressing on the inner (backward, yin) surface; the bow being bent by pulling the string is balanced by the energy of the bow trying to straighten.

LEGS – Right/Left: The rounding of the crotch produces an outward energy that is balanced by the instructions to keep the knees pointing towards the toes (or the big toe in some traditions), which maintains an inward counterbalance to the rounding of the crotch.

Sometimes the outward/inward (right/left) balance is compared to the energy of the legs when riding a horse. When riding a horse, one’s thighs are pressed outward by the animal’s body, but the rider’s knees should maintain inward energy against the horse’s flanks.

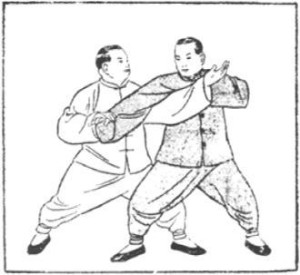

LEGS – Horizontal Plane: Since the knee’s mobility is limited when the weight is partially in the corresponding leg, the movement of the knee is often restricted to just forward/backward and right/left, thus producing the horizontal plane. The forward/backward and right/left balances in the legs are also addressed, at least in Chen style, by the partner practice of knee against knee circles (掤 peng, 捋 lu, 挤 ji and 按 an with the knee).

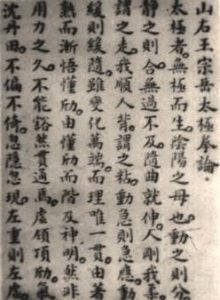

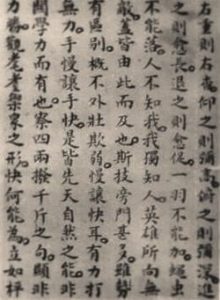

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable.

Taiji [“grand polarity”] is born of wuji [“nonpolarity”], and is the mother of yin and yang [the passive and active aspects]. When there is movement, they [passive and active] become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable. He is hard while I am soft…

He is hard while I am soft…

Wing Chun has lot of practices that develop sensitivity and the ability to feel, it’s very kinesthetic and requires you to be in the moment and aware. This did wonders for my health and stress levels, and opened a whole new world to me. The relaxed concentration used was akin to some forms of meditation, and I just didn’t worry or churn thoughts whilst training or in class. fantastic!

Wing Chun has lot of practices that develop sensitivity and the ability to feel, it’s very kinesthetic and requires you to be in the moment and aware. This did wonders for my health and stress levels, and opened a whole new world to me. The relaxed concentration used was akin to some forms of meditation, and I just didn’t worry or churn thoughts whilst training or in class. fantastic!

n addition to the principles mentioned in the Wikipedia article, I would propose that a major aspect of Taijiquan push-hands is training in the middle range. To transition into fighting with Taijiquan, practitioners may need to practice additional methods not commonly taught in the push-hands format

n addition to the principles mentioned in the Wikipedia article, I would propose that a major aspect of Taijiquan push-hands is training in the middle range. To transition into fighting with Taijiquan, practitioners may need to practice additional methods not commonly taught in the push-hands format