The article Humility is reprinted on Slanted Flying website with the permission of the author Sam Langley from his personal Blog.

If you practice Tai Chi regularly you probably have some sense of gradual improvement. Personally, I find that the better I get the more I practice, and it seems to me that an increase in Tai Chi skill makes you more aware of just how little skill you have. After 8 years of consistent practice I can feel that my body is more connected and more balanced, but at the same time I am increasingly aware of what I’m doing wrong.

Obviously, when we have those eureka moments during practice and a definite sense that we’ve achieved something It feels great. Those moments are in my experience invariably followed, at some point, by a realization that we’re not quite as good as we thought we were.

Anyone who is patient enough to continue practicing for a few years will probably develop a certain amount of humility as it is the only way to get anywhere with Tai Chi. To be regularly corrected by your instructor teaches humility. You start to realize that they can see a whole world of errors in what you’re doing but are only correcting one or two. When I teach beginners I find it best to only give one correction at a time. If you point out to a new student everything they’re doing wrong, chances are, you’ll never see them again. As time goes by, however, we can hopefully become more humble and accept more criticism.

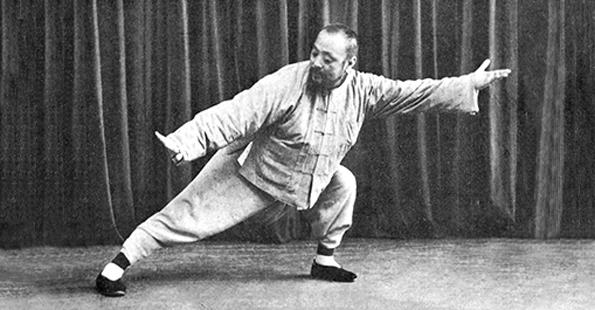

Tai Chi is first and foremost a martial art. You can of course focus on the Qigong aspects and not engage so much in the martial side but I think you’ll miss out on a lot. If Tai Chi can be a spiritual endeavor, it is through dedicated practice of Tai Chi as a martial art. Some people are uncomfortable about practicing a martial art as they don’t want to be involved with anything violent. In my experience martial arts generally and Tai Chi in particular make people less violent. Only by gaining an awareness of our dormant aggressive and defensive tendencies can we overcome them.

Pushing hands exercises are often where we are forced to learn some humility. It becomes apparent early on that brute force hinders you and that only by listening to people and learning to lose over and over again will you get better.

Why do you want to get good at Tai Chi anyway? Do you want to look impressive in the park? Do you want to be really good at fighting? Is it an ego boost? I find it interesting to ponder these things, and regardless of ones initial reasons for taking up Tai Chi it does become something to do for the pure joy of doing it. My current reason for getting better is, I think, because the physical sensations are more satisfying the better one gets…..and in a way I’m starting to enjoy those moments of awareness that I’m not quite as good as I thought I was.

Tai Chi Chuan is often described as meditation in motion. With this feature, the simultaneity of physical action and the achievement of a meditative state of awareness, Tai Chi Chuan has become famous. This fusion of inner stillness and outer movement leads to a special feeling. One is in the here and now, highly concentrated. All the worries of everyday life are forgotten and it simply feels good. The own body, breathing and the change of movements are perceived without being focused on it. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi saw this kind of inner experience also in artists at their work. He named this state flow experience and investigated it in further studies.

Tai Chi Chuan is often described as meditation in motion. With this feature, the simultaneity of physical action and the achievement of a meditative state of awareness, Tai Chi Chuan has become famous. This fusion of inner stillness and outer movement leads to a special feeling. One is in the here and now, highly concentrated. All the worries of everyday life are forgotten and it simply feels good. The own body, breathing and the change of movements are perceived without being focused on it. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi saw this kind of inner experience also in artists at their work. He named this state flow experience and investigated it in further studies.