I recently wrote an article about four training mistakes often seen in Pushing Hands (Tui Shou or 推手). That article was intended to educate people so that they could strive to be better partners. But what happens when you’re the good one, but your training partner is not? Training with partners of any kind will eventually lead to being paired with someone that keeps making mistakes, has their own agenda, or is too caught up in their ego to be a good partner. What do you do then?

Obviously before you say anything to your partner, you have to make sure that you aren’t guilty of the same problem behaviours. Sometimes it’s easy to fall into a competitive cycle, which escalates because of your own involvement. So, always remind yourself that you are there to learn how to avoid falling off balance, rather than to prove you are better than someone else is.

Once you’re sure you aren’t instigating or escalating the troubling behaviours, the best solution is to talk to your partner. Tell your partner about your training goals and enlist their help in achieving them. Saying something like, “I need to go slowly today because I’m working on developing better timing,” is often all it takes to get your partner to stop and think.

However, sometimes friction between partners comes about because one of them feels threatened by the other. If you find yourself in this position, it’s important to remember that your partner may not even be consciously aware of this. They may not realize how much you bring out the competitive streak in them.

However, sometimes friction between partners comes about because one of them feels threatened by the other. If you find yourself in this position, it’s important to remember that your partner may not even be consciously aware of this. They may not realize how much you bring out the competitive streak in them.

best solution to this problem is that you have to remove any threat they feel from you. In these cases, it’s helpful to say something like, “You keep pushing me over using this or that technique and I’m having real trouble defending against it. Do you have any suggestions?”

By doing this, you’ve effectively announced that you’re not competing with them, but rather trying to improve your skills. When your partner isn’t feeling threatened by you, their behaviour can and often will significantly change.

You also have to realize that you may be in a completely different place (emotionally, spiritually, and even training level) than your partner. Sometimes people are stuck at one phase of learning and aren’t ready to improve yet. It won’t help to get mad or impatient with your training partner if they keep repeatedly making the same mistakes. You have to realize that this is their challenge to overcome and they just aren’t ready yet.

If this is happening, you sometimes just have to remind yourself that you aren’t going to Pushing Hands with this person forever, and just do your best while you wait for the next partner to come along.

Sometimes you may find yourself paired regularly with a partner who just doesn’t get it, is too aggressive, or is otherwise a problem for you. If this happens, you may need to have a private word with your teacher, but don’t be accusatory or confrontational about it. Sometimes teachers pair partners together when they think that one or both can learn from the experience. Even if your partner is the one exhibiting bad habits, you may be the one who needs to learn how to deal with this without losing your temper.

Even if your teacher didn’t pair you with a frustrating partner on purpose, you can often look at your work together as a way of overcoming your own anger and frustration issues. Often anger and frustration may be a big obstacle to your own skills advancing. Once you overcome your own frustration, you may find that whatever bad habits your partner was exhibiting don’t matter anymore. You may even find that, in dealing with your frustrations, you are now capable of neutralizing the techniques that were once a problem.

Trust issues, bad relationships, anger, and even trauma caused by other people all have one thing in common: conflict. It doesn’t matter if the conflict is physical or emotional, our body’s reaction, and our resolution skills are often the same. One of the main reasons for this is that the brain does not differentiate between physical or emotional conflict. When we perceive either, our body reacts by dumping hormones and activating muscles preparing our body for one of two very primitive responses. When faced with danger our body prepares either to fight or to run. This is affectionately called the “Fight or Flight” response.

Trust issues, bad relationships, anger, and even trauma caused by other people all have one thing in common: conflict. It doesn’t matter if the conflict is physical or emotional, our body’s reaction, and our resolution skills are often the same. One of the main reasons for this is that the brain does not differentiate between physical or emotional conflict. When we perceive either, our body reacts by dumping hormones and activating muscles preparing our body for one of two very primitive responses. When faced with danger our body prepares either to fight or to run. This is affectionately called the “Fight or Flight” response.

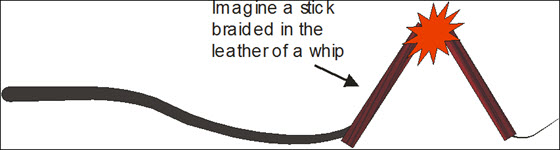

On the surface, this appears to be a way of categorizing the multitude of techniques and application found in Chinese martial arts. While it is true that these categories cover every possible technique employed in hand-to-hand fighting, there is more to this than simply labeling categories. These groupings are arranged to teach a basic and profound logic in how fighting works.

On the surface, this appears to be a way of categorizing the multitude of techniques and application found in Chinese martial arts. While it is true that these categories cover every possible technique employed in hand-to-hand fighting, there is more to this than simply labeling categories. These groupings are arranged to teach a basic and profound logic in how fighting works.

Sadly, and particularly here in the United States, I have noticed a huge obstacle to this type of mastery.

Sadly, and particularly here in the United States, I have noticed a huge obstacle to this type of mastery.